Throwback Thursday #7 - The Great Unclimbed II

In The Climber issue #72 (winter, 2010) a feature ran with six of the last great unclimbed lines in the Southern Alps—The Great Unclimbed. Multiple authors identified major prizes, such as the west face of Mt Tutoko in winter, or the south-west face of Mt Percy Smith in winter. While those two routes were soloed by Guy McKinnon and Ben Dare respectively in the subsequent years, not all these prizes have been claimed. Today we revisit Nick Cradock's contribution on the east face of Pope's Nose direct.

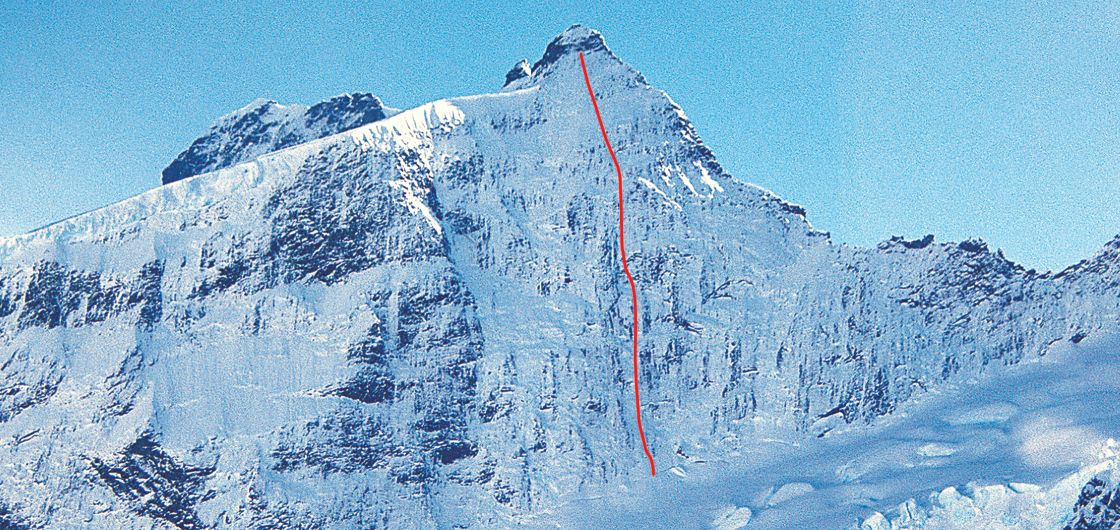

The East Face Of Pope's Nose Direct In Winter

The Warm Up: A new route on the north face of Mt Hicks

In July 1987 Paul Aubrey (of Moonflower Buttress fame) and I accessed the head of the La Perouse Glacier via Harper Saddle. We bivvied and the next day tried to climb the steep mixed gully between the Left and Right Buttresses on the north face of Mt Hicks. I had first spied the gully the year before while climbing Weeping Gash (VII, 5+) with Guy Cotter (the left-most gully on the face). The climbing was too hard for Paul and I though, so we bailed out by climbing up the North-West Spur and descended back to Empress Hut.

The next day we climbed Heavens Door (V, 5+) on the south face and abseiled The Curtain (IV, 3+) descent gully in excellent, safe conditions.

The route on the north face has not been tried again.

The commitment level required for this route (with the abseils into the La Perouse Glacier and the remoteness of the face), makes it a perfect warm up for the East Face of Pope’s Nose Direct.

The route could possibly be done in a day return from Empress Hut, but considering the short daylight hours of winter, the difficult access and the fact that most New Zealand climbers completely lack any experience on long winter climbs—a bivouac will probably be necessary. This ain’t day cragging at Pioneer.

The first few pitches will probably present the technical crux; accessing the gully proper from the base will require climbing a discontinuous icicle that hangs down a steep orange wall. When the rock is orange at Mt Cook it usually means it will be good quality, but pro will be sparse.

ROUTE INFO:

Height of face – 600 metres

Aspect – north facing. Temperatures must be very cold to mini-mise objective danger from falling rime and rock.

Best time of year – June or early July.

Type of route – steep, modern-mixed, remote, committing.

The Real Prize:

The Direct line on the east face of Pope’s Nose in winter is, without doubt, the preeminent unclimbed line in New Zealand.

Despite numerous attempts by Allan Uren and others in the years since the first ascent of the face in 1990 (FTP [VI, 6], by Brian Alder, Dave Fearnley, Lionel Clay and myself), no one has managed to even climb the face again in winter, let alone climb The Direct, let alone climb the mountainz.co.nz forum uber-fantasy: a combination of a winter ascent with another route on Mt Aspiring. (Note: Guy McKinnon made an audacious walk-in solo ascent of the face after this article was originally published, though the author suggests this ascent should be considered as a repeat of FTP, rather than the the prized line discussed here.)

There is no doubt that a winter ascent of the East Face of Pope’s Nose would look good on anyones CV, and climbing The Direct would be the prize of the decade.

The face is approximately 700-metres high, topping out at 2700m and it faces east-south-east. The best time to climb it is any time from early June to early August. There doesn’t seem to be any particularly favourable weather patterns that set the face up. There is no guarantee of finding good conditions. In my experience, good ice and rock protection are two things that are few and far between on this face. Out of the four or five attempts that have been made on the face, at least two have failed because of soft ice. If it is cold, the face is white, the forecast is bomber and snow conditions are stable—you just have to go and find out what it’s like on the day.

The traditional thinking has been that a full white line will offer the best climbing conditions. However, attempting the route in early June—before low and deep snow becomes an issue —could provide conditions where more rock is exposed, which, depending on your point of view, could be a good thing.

The face sports some seriously good real estate, if you like that kind of landscape. The Direct is a consistently steep line offering committing, insecure, technical mixed climbing with sparse protection in a savage and remote environment, direct to the summit. Conditions can be variable and you will not know the true conditions on the day until you try the face. If you don’t try you won’t know.

Walking in is a noble option, however it can also be used as an excuse for failure and for not attempting the true crux (the actual face). Bailing out possibilities are either to access the col between Pope’s Nose and Scylla and then go up the snow ramp on the northern side to the top of Pope’s Nose and down the Bonar Glacier and French Ridge, or to go down and around the Kitchener Glacier to underneath Moncreiff Col, then down a steep bush spur to Aspiring Flat. Both of these options have been done succesfully before, neither are very relaxing in deep snow, but they present no real technical difficulties.

Prior Preparation

- Pin up pictures of the routes in your house. Get obssessive about climbing them, to everything else’s detriment.

- Find at least two good partners who are: (a) reliable; when they commit to a project they don’t back out (keep in mind that it is highly likely that one person will drop out). The worst case scenario here is that you end up with a very strong team of three—which is still good and (b) preferably climbing harder than you are. Surround yourself with talent.

- Set aside time and money for the climbs. Everybody will need to be flexible around the weather for June and July.

- Get fit, organised and super motivated.

- Keep track of conditions.

- Live the climb.

How To Climb It

- If you want to walk in on your attempt, I’d suggest the best route is via Aspiring Flat and the Kitchener Glacier. You could fix a couple of pitches, camp on the glacier in comfort, then blast for the top the next day. Descent would entail abseiling back down the face to your gear and continuing back to Aspiring Flat. This would probably take four days.

- Take a battery drill, one battery (know how many holes it does), bolts (75 x 10mm) and a new drill bit. You may never need to use it, but it will give some options for non-existent anchors.

- Three people is possibly the way to go: the leader does not want to be climbing with a heavy pack (or any pack on some pitches).

- Climb pitches in blocks, one person jumars.

- Take leashless tools.

- Descend via French Ridge.

By Nick Cradock