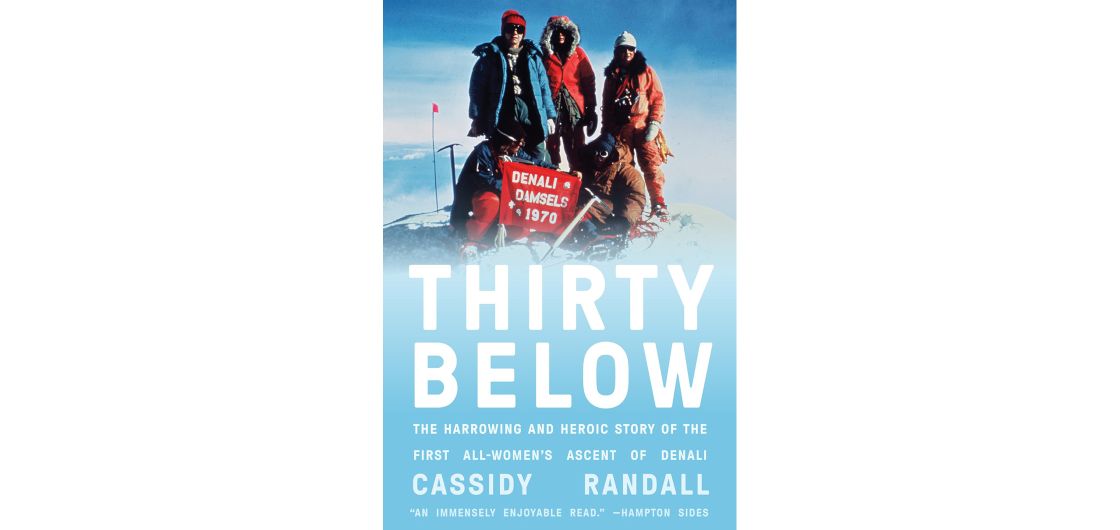

Thirty Below - A New Book Featuring Margaret Clark

In 1970, Christchurch mountaineer and geologist Margaret Clark joined the International McKinley Women’s Team, also called the Denali Damsels, in the first all-women’s attempt to summit Denali—or any of the world’s big peaks. They were led by Alaskan climber Grace Hoeman with California climber Arlene Blum as deputy leader. Californians Margaret Young (M.Y.) and Dana Smith, and Australian Faye Kerr made up the rest of the team. On July 6, fifteen days into their expedition, they made their attempt at the summit.

On the steep three-hundred-foot ice slope that led out of Denali Pass, a sound like a pistol shot cracked through the incessant roar of the wind. Everyone froze. In the mountains, such abrupt sounds make the stomach drop, the heart skip a beat, the breath stop. On a steep snow-covered slope, a loud whumpf is the snowpack collapsing, about to give way beneath your very feet to avalanche. A pistol shot can mean bridges over hidden crevasses failing. Such sounds mean instability, danger, and the entire body reacts to them. There wasn’t enough snow on this scoured slope to give way into an avalanche, and orange wands remained from another team that marked a route free from crevasses. Still, the women moved more carefully in deference to the cracking.

In the back of the line, Margaret concentrated on her breath. If she opened her mouth, she started coughing. If she stopped, she started coughing. If she changed her breathing pattern, she coughed. She couldn’t understand it. Could her body be betraying her like this already, so soon after the multiple sclerosis diagnosis? She focused on taking one step for every three breaths, and for each breath, she wiggled her toes twice. It was the only way to keep the numbness at bay. Even through the counting and concentrating, the rocks intrigued her. Black basalt and pink granite reared through the snow and ice. She wished she could stop to examine them and take samples. The way back down after they’d summited, she told herself, would be a better opportunity for that.

They stopped a few times to rest and try to eat. It was a chore to force anything down. The chicken livers and salami they’d brought were frozen, as were the water bottles. Most of them couldn’t face crackers without water to wash them down. They managed a handful of dried peas and some candy bars, and stuffed what they could in their jackets to thaw out.

Grace felt too exhausted to eat anything. Her mind had become fuzzy, but she believed she was still in a passable state to continue—if she could just hurry up and make it to the top, she could be on her way back down and recover on the descent. She was hardly the first climber to push for the summit while suffering altitude sickness, hoping to beat the effects of altitude by heading quickly for the top and then descending before symptoms become dire. But the others had each privately begun to worry for Grace. She didn’t appear to recover at these rest stops.

Grace felt her steps becoming more effortful. The pills she’d taken didn’t seem to be working. Her head had begun to split like someone was taking a hammer to it. She forgot her training and experience. Instead of moving slowly and consistently, she began to hurry for several steps to keep pace with her teammates, and then stopped to lean over her ice axe to catch her breath.

Just below Archdeacon’s Tower, Margaret stopped to change the film in her camera. When she caught up to the others, they were stopped on a flat outcrop of pink granite that practically glowed in the sun. They all took off their packs to lay back on them and doze for a moment of rest. When Margaret woke, the others were already setting off. No one had called to rouse her or tell her they were leaving. To Margaret, it was a sign that there was no group cohesion—let alone any leadership. Grace was solely focused on getting one foot in front of the other. Arlene had yet to say anything about the older woman’s concerning state, or to bring the group together as a team in the absence of Grace’s leadership. The younger woman was still hoping she wouldn’t have to.

At two in the afternoon, their strung-out line finally topped the ridge that led to the summit. Beyond the flat of the ridge, the zenith of North America rose, a rounded snowy point soaring into the blue. From the relatively flat field of the ridge on which they stood, the last rise beyond it to the summit seemed a mere jaunt compared to the many thousands of feet they’d already climbed. And yet they knew that the last hill to the top would the worst part, as they were already so tired and rocked from the immense altitude and cold.

Margaret and Arlene had been watching Grace’s erratic progress. Now they turned to each other to discuss as they made their slow way forward.

“If she’s already staggering like this on flat ground, how is she going to get up that last slope?” Margaret said.

Arlene had no answer. She worried for Grace, but she also found herself annoyed that the older woman wouldn’t just admit she was sick and turn around. And there was no talking the matter over with the others. M.Y. was far ahead, seemingly on her own and totally disengaged from group dynamics. Dana was behind her. Then came Faye, averse to conflict—although she did stop frequently to rest, and to stay close enough to keep an eye on Grace. And so it was only Arlene and Margaret, who had already decided to stay behind Grace in case she worsened, who could see how badly the Alaskan was deteriorating.

The route on the slope zig-zagged around a section of crevasses. As Margaret slowly marched upward behind Grace, she realized that if Grace did, against all odds, reach the summit, there was only one likely outcome from there. Her manic drive would evaporate right after, and the rest of the team would have to carry her down. It would be a race against the savage cold and the oxygen-depleted altitude. They’d barely eaten anything today. They’d drank next to nothing from frozen water bottles, only what hot liquids they had, and those were running out. How much stamina would they have left to get her down from this perilous high sweep?

Margaret stopped focusing on the spectacular rocks and the otherworldly view from the top of the world. Instead, she began analyzing the slope as something down which to haul an incapacitated person. All enjoyment of the climb had fled. In its place, Margaret began to feel a sense of impending doom.

***