Uprising - Book Review

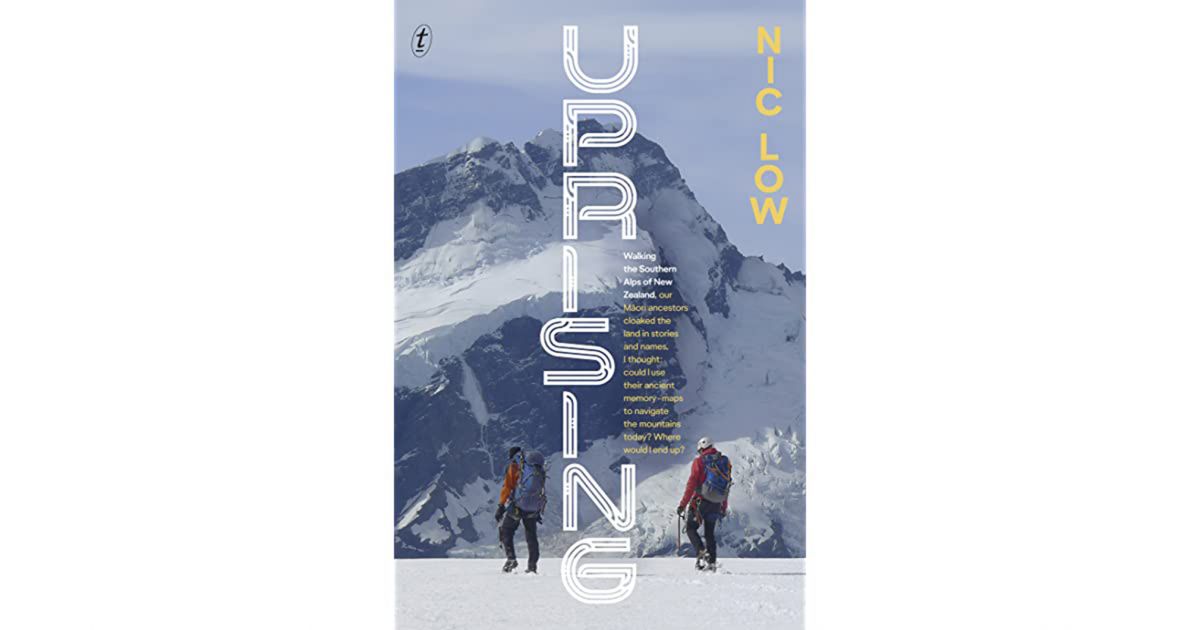

Uprising. Walking the Southern Alps of New Zealand by Nic Low. Text Publishing, Melbourne Australia.

Review by Ross Cullen

Nic Low has written a terrific book after five years of research that included walking, climbing and paddling the mountain lands and rivers of Te Wai Pounamu. Through these trips, Low spent time exploring, considering, learning, understanding how his Ngāi Tahu ancestors revered, travelled across, lived in this land of forests, grassy plains, stony riverbeds, foothills, glaciers, peaks and passes, its backbone the 500km long Kā Tiritiri-o-te-moana. For this Kiwi who has rarely encountered in the hills or climbed with takata whenua, Uprising is a revelation.

Nic Low grew up in Christchurch, where he could see the foothills and occasionally mountains in the distance, heard legends of mountain travel and exploration, but for thirty years pushed aside learning and real understanding of Māori relationship with the whenua. Over the course of nine chapters, Low reports how this changed as he learned from tribal leaders and scholars, dug into iwi and other archives, opened and read a family memoir and then took the knowledge thus gained on more than a dozen crossings of the Southern Alps. On these trips he tested the ideas recorded in tribal lore and sought to understand the logic embedded in iwi memory and accounts of past events and ara tawhito – traditional travel routes including journeys across mountain passes.

One of the most memorable sessions at the 2016 Sustainable Summits conference held at Aoraki/Mount Cook centered on Māori names for geographic features in Ngāi Tahu’s takiwā (Te Wai Pounamu south of about 41.30º S). That early demonstration of Kā Huru Manu—the Ngāi Tahu cultural mapping project, was a conference highlight, startling many present with the volume of placenames bestowed by Waitaha, Kāti Māmoe and Ngāi Tahu iwi. The origin of placenames can stem from several sources, some are descriptive and modern—Mount Hiwiroa with its long ridge, or older but still descriptive—Maungakura with its red rock. Some may be descriptive—Aoraki the cloud piercer—but also repeat earlier use, Aora’i is the second highest peak in Tahiti.

Nic Low alerts us that many Māori placenames are part of an oral map recounting travel through a region. Perhaps most famously for Ngāi Tahu, the journey of Raureka from her home on the West Coast up the Arahura River to Nōti Raureka (Browning Pass), down the Wilberforce River to Whakamatau (Lake Coleridge), and out onto Kā Pākihi (the Canterbury Plains) and eventual meeting and display of her toki pounamu to Ngāi Tahu men hewing a canoe with inferior tools near Te Umukaha.

Motivated by such stories, Low sets out to retrace the traditional trails through the mountains, sometimes alone and sometimes with companions, testing the legends, speculating on how Māori were equipped and provisioned for those journeys and seeking to understand each oral map‘s logic. Along the way, he gets to weave in myths, history, wars, European arrival, ambition, a treaty, land claims, purchase agreements, promises shamefully broken, loss of most Ngāi Tahu land and dislocation particularly from high country, decades of effort seeking redress for past wrongs, heroes in that struggle, a flagship leadership project Aoraki Bound and other Ngāi Tahu renewal projects.

There are also chunky chapters on a solo walk up the Godley valley and avalanche ride near Sealy Pass, trips over Rurumātaiku (Whitcombe Pass), Tarahaka (Arthur’s Pass), Nōti Hurunui (Harper Pass), Nōti Hinetamatea (Copland Pass) a slog up the highway to Tioripātea (Haast Pass) a successful ascent to near the summit of Aoraki, boat and foot travel carting pounamu from Fiordland to Southland (Te Rua-o-te moko Ki Murihiku), interesting insights into the lives and behaviour of Leonard Harper, his son Arthur and plenty of other Europeans lured into mountain journeys chasing fame, fortune or other reward. But what I found most thought-provoking are Low’s frequent observations on current names and interpretation that ignore earlier events and placenames. He walks around Lake Coleridge noting a sign explaining how lightning struck a Macrocarpa tree on Saturday 22 January 2000, but fails to find any record of Raureka’s journey or any trace of a 14th century moa hunters campsite.

Uprising is a wakeup call to complacent people like me, and perhaps you, if you have not bothered to do much more than remember to say Kura Tāwhiti or Tititea when selecting a climbing region. There are hundreds of ancient stories about Aotearoa and learning some of them is rewarding if the insights gained by reading Uprising are a good indicator. Don’t be deterred by the thought that that Uprising is woke and arouse angst. Nic Low is one of us, keen on beer and a pie, attracted to a woman and now a parent, unable to tear himself away from the window on Christchurch-Melbourne flights (ask to be seated on the left side flying west, right side flying home). Uprising is carefully researched, well-written, makes dozens of astute observations, enjoys taking the piss and takes New Zealand mountaineering literature to somewhere new and overdue.