Keeping Warm And Avoiding Hypothermia In The Mountains - Part One

by Gregg Beisly

Winter has arrived and many of us will be out in the hills having fun and the occasional epic that will be fun in the retelling. Before you get on the snow and ice, make sure you are schooled up on keeping yourself safe.

In this three part series we will look at how to keep warm, understand hypothermia and manage an emergency situation in cold conditions.

Part 1 Staying Warm

Key Points:

| Fitness helps you sustain activity, which keeps you warm. Take equipment and wear clothes that you know work for the conditions expected. Test it before really needing to rely on it. Take enough food and drink to keep hydrated and energy levels high. Understand how hypothermia and cold injuries occur and their symptoms.

|

| Avoid getting wet from sweat—vent, remove layers, moderate activity. Avoid getting wet from rain or snow—take a good waterproof outer layer. Wear fabrics that move water away from your skin and dry fast.

|

| Make sure you have a layer that completely blocks wind.

|

| Wear active wear layers that will minimise sweating. When you stop, trap warmth generated from activity by putting on an insulating layer.

|

| A mix of carbs, protein and fat gives immediate and long lasting energy.

|

| Dehydration increases risk of cold injuries and hypothermia.

|

| Alcohol dilates blood vessels in the extremities, drawing warmth away from the core, where it is needed.

|

| Understand how your body works and what it needs to stay warm. This might be quite different from others you climb with. |

For those of you wanting a deeper understanding of keeping warm in the hills, read on.

The Cold Equation

The Cold Equation

Whether someone is hot, warm or cold can be summarised as:

Heat production + Heat retention – Cold factors = Cold or Hot climber

Heat production: Exercise (limited by fitness, fluids, food), person’s metabolism and fuel stores.

Heat retention: Body shape/size, body fat, insulation, dryness, wind protection.

Cold factors: Temperature, wet, wind.

Heat production

Your cells produce heat, via metabolic processes, which is increased during physical activity. Metabolic processes work best at 37°C. Core temperature is what is important for overall metabolic processes in the body. The temperature of the extremities is not critical and blood flow to outer limbs is restricted in order to maintain stable core temperature.

The amount of heat produced, and how long it can be produced for, is limited by a person’s natural metabolism, their fuel stores (glycogen stored in the liver), fitness and food and fluid intake. The fitter the person, the longer they can sustain heat producing activity. Also, endurance training improves the body’s ability to burn fat, allowing increased activity levels for a longer period. It is difficult to keep glycogen levels high over an extended period of exercise although frequent food intake can help. The right mix of fuel for the cells—glucose, protein and fat—means more heat can be produced for longer.

The whole system runs more efficiently when fluid levels are at optimum. Further, a dehydrated person is more susceptible to cold injuries and hypothermia due to reduced fluid volume.

Heat Retention

In order to know how to retain heat in cold conditions, it is useful to understand how we lose it.

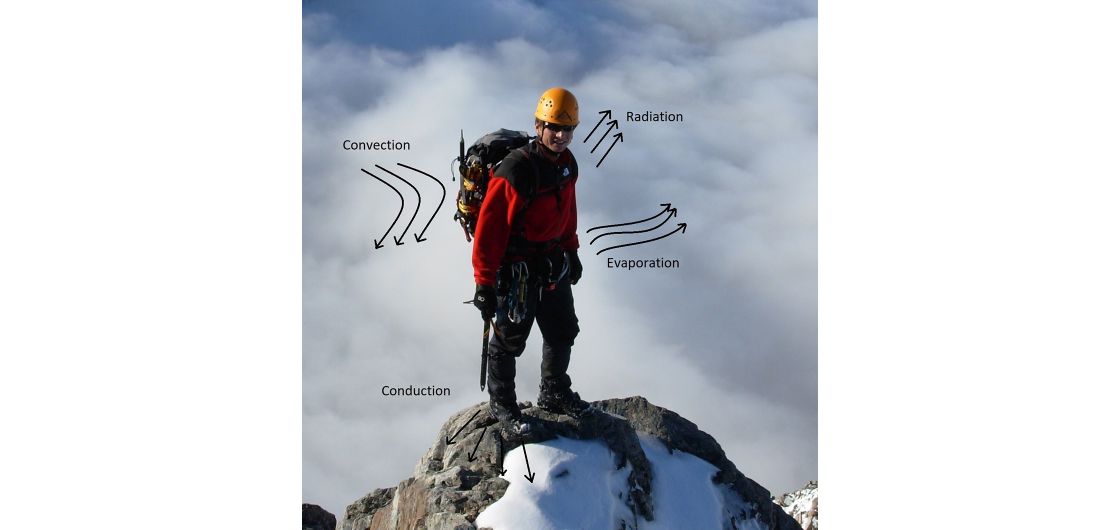

Our bodies lose heat to the environment in four ways. Radiation, conduction, convection and evaporation.

Radiation accounts for the majority (about 60%) of heat loss in a dry person in average weather conditions. Other processes start becoming more important as wetness and wind are added.

Radiated heat can warm air pockets trapped in clothing. Wet clothing replaces air with harder to heat water, reducing heat retention. Keeping clothes dry is the aim.

Conduction, the transfer of heat between solids when a temperature gradient exists, usually accounts for a small amount of heat loss in a dry, standing person. Wet clothing increases that x5 and if more of the person is in contact with cold ground/rock/snow, then this increases further.

Keeping clothing dry, especially layers next to the skin, and insulating from the ground are important here.

Convection occurs when one set of molecules are in motion. These move against a surface, are heated by conduction, move away, and are replaced by new molecules which are also heated. The rate of heat loss via convection depends on the density of the moving substance (water convection occurs more quickly than air convection) and the velocity of the moving substance (higher winds = greater heat loss).

Blocking wind is important for minimising heat loss from convection, as is staying dry.

Evaporation

When we sweat, we cool down by moisture on our skin evaporating, as heat is lost when water is converted from a liquid to a gas. Evaporation increases in dry, windy conditions and when the skin or clothes next to the skin are wet.

Decrease evaporative heat loss by adding a wind blocking layer and by keeping the skin and base layers dry.

Additional Heat Retention Factors

Alcohol is a vasodilator, which increases blood flow in the extremities and pulls warmth away from the core and so is a negative factor when it comes to retaining heat.

Caffeine is a diuretic and so causes fluid loss from increased urination. This increases the potential for dehydration which results in greater risk of hypothermia and other cold injuries such as frostbite.

Clothing and equipment for cold weather

With knowing how we lose and retain heat, taking the right clothing and equipment for cold conditions should become clearer. Dressing for the mountains is the art of trapping the right amount of heat, while staying dry. A layering system assists by allowing adjustments to either let heat escape, and so prevent wetness from sweating, or trapping more heat and blocking wind and wet from without. Whatever combination of clothing and gear you end up with, test it all out in difficult conditions close to the road or shelter before having to rely on it far from help.

Base layer: Your next to skin layer should be made of fabric that assists in moving water away from your skin. Merino, polypro and polyester all do well at this. Be aware that merino can hold up to 15% of its weight in water before it feels damp. This might be good from a comfort perspective, but water is a good thermal conductor so merino typically has greater conduction loss, meaning it will be colder when wet than the synthetics. Merino also takes longer to dry.

Mid layer(s): There are many options for mid layers depending on how cold things are expected to get and the activity you are doing. A thin fleece and soft shell combo is good for blocking wind while being breathable and versatile for when doing highly aerobic activities.

Insulation layer: Particularly in winter conditions, a very warm layer for when stopped, especially at belays or bivvies, is required. If at elevation with a high freezing level and no rain expected, a quality down hooded jacket is great. If things could get wet, a synthetic option will be warmer if damp.

Wind/water proof layer: Most alpine jackets and overtrou are made with a membrane or other waterproofing that lets water vapour pass through, reducing dampness from sweating. If you are exercising hard enough or conditions are humid, that won’t be enough and the ability to vent via pit zips or other design features is helpful.

Hat: We lose a lot of heat through our heads so a good bit of insulation on top is vital.

Neck gaiter/buff: Stop heat from escaping around the neck and cover the face when things get wild.

Gloves: These get wet easily so having spares is important. Some gloves have a lining that is difficult to get into when your hands are damp, so test this before you are far into the backcountry. Mitts keep fingers warmer when it gets really cold.

Feet: Wear alpine boots and lace them so they are firm but have no single pressure point that might constrict blood flow. Good socks will help and gaiters can add a bit of warmth to boots, as well as keep them drier.

Emergency gear:

- A shelter such as a lightweight bothy bag can be a life saver.

- Insulation from ground such as a section of closed cell foam.

- Spare insulation layers within a group—injured or sick people get cold much faster than the uninjured.

Extra tips for really cold conditions or those who get cold easily:

Fill a narrow Nalgene bottle with hot water and put it in an inside jacket pocket. Make sure it has a watertight seal.

Have food handy when climbing and at night.

If standing around at a belay or for another reason, keep heat production up with some activity. Deep squats with arms out and pumping (think ‘milk the cow’) or similar exercise can generate plenty of warmth.

Hand warmer sachets in gloves or boots can help those who have poor circulation.

If in a group in windy weather, make a ‘penguin wall’ to shelter someone needing to stop for some reason, rather than standing around separately. To do this the rest of the party stands tightly together with their backs to the wind, shoulders overlapping, creating downwind shelter.

Summary

Keeping warm in the outdoors starts with understanding the challenge of cold conditions and preparing for it. Planning for cold can start with ensuring general fitness for the hills before a trip, having the right equipment and clothing for the conditions and taking a good mix of food and fluid.

While out on a trip do your best to stay dry, dressing to avoid getting damp from sweat, rain or snow. Keep hydrated and maintain a good food intake. Be aware of how you and others in your group are coping with the conditions.

In Part 2 we will look at hypothermia and how to avoid and treat it.

Really great articles these… concise and relevant, thanks

Pagination