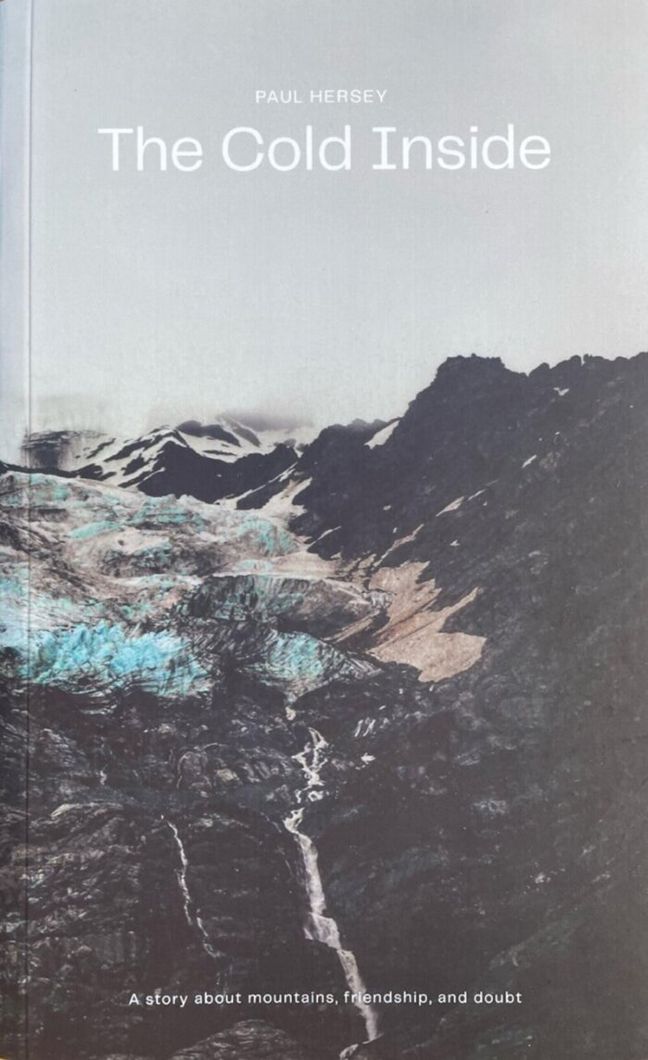

The Cold Inside Book Review

The Cold Inside, by Paul Hersey

Review by Derek Cheng

There's a curious passage—in italics—in the middle of Paul Hersey's book The Cold Inside where a climber embarks on a solo mission to a seaside pinnacle to soothe his broken heart, and, having topped out, lies down and awaits hypothermia.

It sits between parts one and two in the book and, at first glance, seems to come from nowhere and serves only to confuse.

But dig a little deeper and you might find multiple threads at play. Maybe the climber awaiting the Grim Reaper is coming to grips with the cold inside himself. Maybe we all have felt such a frigid inner core at some point, triggered by heartbreak or grief, or by some gut-wrenching exposure, or by having been driven to the edges of mental and physical capabilities, with an uncertain outcome still ahead.

These are all common themes in a well-written book that is part memoir, and part exploration into the age-old question of why climbers climb.

On the former, Hersey takes the reader through his introduction to climbing, his early fascination with a Nugent Welch oil painting of the Mackenzie Basin with mountains looming in the background, his love of climbing books and stories, and his first forays into the hills with his brothers.

On the latter, Hersey offers a well-researched investigation into what he calls the 'sublime state' that climbing delivers. Part of it is connecting with nature: how climbers are drawn to interact with the mountains—or particular parts of particular mountains—rather than simply admiring them from afar. Part of it is an element of risk and uncertainty: 'Let them take risks, for godsake, let them get lost, sunburnt, stranded, drowned, eaten by bears, buried alive under avalanches—that is the right and privilege of any free [person].' (Hersey quoting American environmental essayist Edward Abbey).

In the right frame of mind and in the right circumstances, Hersey writes about how 'the exposure of falling was something I could almost embrace' and climbing up 'without fear of the consequences should I slip'.

These are often fleeting moments. Hersey also shares those moments when doubt and fear creep in.

As his climbing progresses, there are excellent adventures. There are close calls. And then there are those who don't make it home.

Hersey jumps effortlessly from trying to answer the deeper questions about why climbers embrace the mountains—and the objective hazards that always accompany them—to his own experiences among them. Some provoke further questions; his telling of an expedition to Pakistan with Pat Deavoll is so full of contempt that it immediately made me wonder what her version would be. Others are tales of being gripped on a wall above questionable protection that will not be unfamiliar to anyone who has read a climbing story.

The most powerful passages, for me, were the ones where Hersey shares the most of himself: the raw, visceral emotion of losing a loved one with whom he has shared many ropes.

These are especially brought home because Hersey pays careful attention, over several chapters, to building up their personalities and values, as well as their climbing strengths. It's a testament to Jamie Vinton-Boot and Marty Schmidt that they dominate much of the book: their philosophies, how they progressed as climbers, and how Hersey valued his interactions with them both on and off the mountain.The clear message is that the bond between climbing partners is a huge part of the formula that can lead to the 'sublime state'.

In facing his grief, Hersey pondered the what ifs, turned his back on his climbing tools, explored various coping mechanisms—including writing a passage about climbing to the top of a sea stack and then lying down into hypothermia's grip.

He sought solace in the company of the relatives of those who died; Schmidt's daughter tells him, 'If [Dad] ever stopped climbing, his soul would shrivel.' Better to have a vibrant soul than a shrivelled one, even if that means taking on risks you otherwise wouldn’t.

Hersey's return to climbing is his reconciliation with grief, and with the questions surrounding why he ventures into the mountains in the first place. It's a search for just the right amount of risk to feel the vibrancy of the soul, but not so much that there's a decent chance of not coming home.

It's his coming-to-terms with the cold inside, including his acceptance—or even his embracing of—the uncertainty of choosing to continue climbing upwards.

The italics passage in the middle of his book alludes to a passage in the beginning, also in italics, where Hersey asks about the rights or wrongs of climbing, and who gets to say.

Not God nor the Devil, he decides, but 'only the greyness within ourselves and a choosing that is not so certain'.

The Cold Inside, by Paul Hersey, is available from the NZAC Webshop.