Throwback Thursday #5 - Axes Of Evil

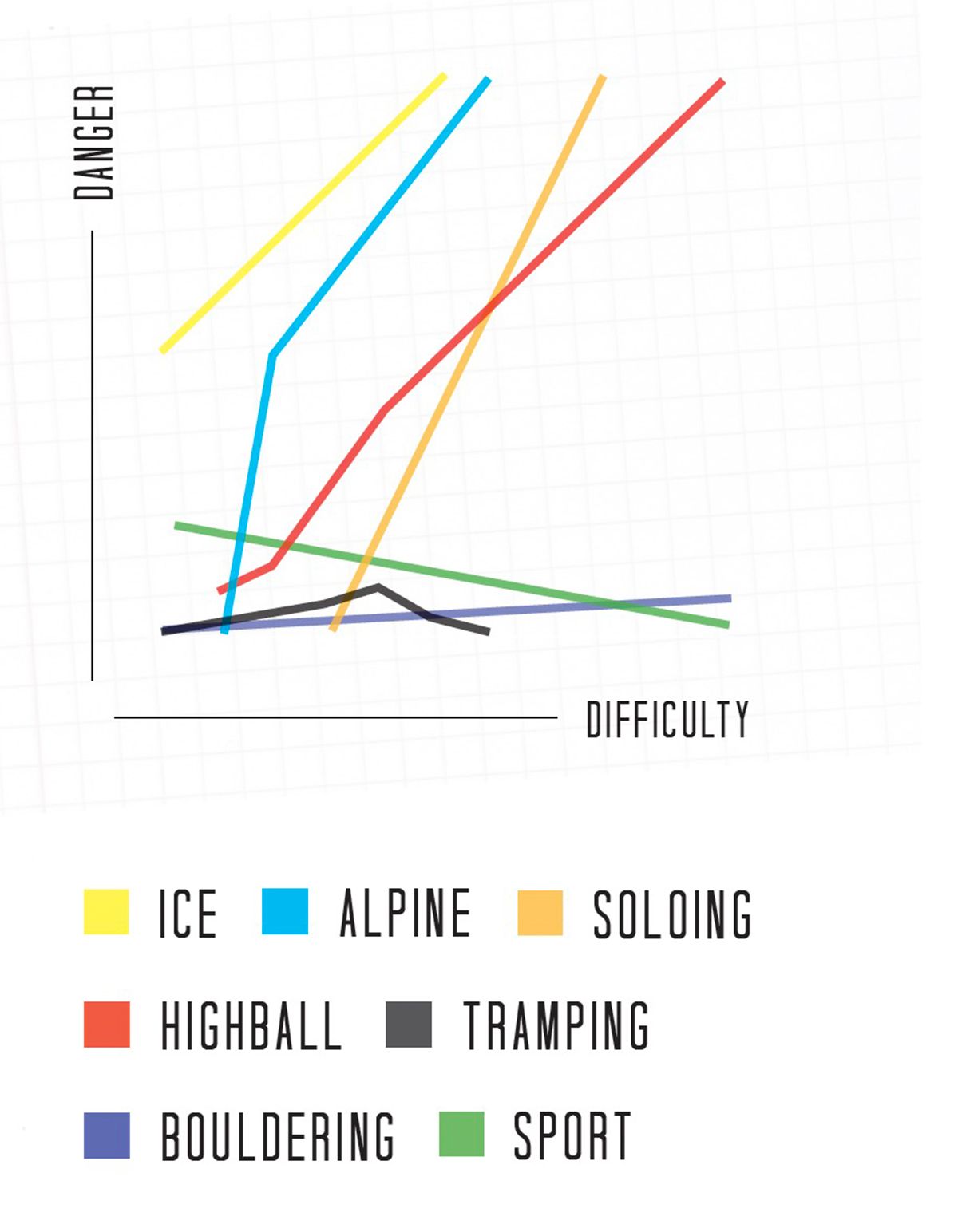

Whatever, whoever, wherever—climbing has only two dimensions: difficulty and danger. Don’t believe the hype when people tell you that climbing is about communion, with nature and each other. Or that it transcends mind and body. People who say that stuff are usually trying to sell you hemp shoes (a bad idea, on so many levels). Climbing is none of those things. It may be a medium for self-expression and self-absorption, but really, climbing, in all its declensions, is only about the axis of difficulty and the axis of danger.

Against those two axes, climbing history and progression can be plotted. And so the various sub-genres of climbing can be ranked, to determine which is king amongst kings. Whichever achieves the highest intersection of difficulty and danger must, by definition, be the ultimate expression of the art form that is climbing. Sure as eggs.

Against those two axes, climbing history and progression can be plotted. And so the various sub-genres of climbing can be ranked, to determine which is king amongst kings. Whichever achieves the highest intersection of difficulty and danger must, by definition, be the ultimate expression of the art form that is climbing. Sure as eggs.

Some may be surprised by the results, but the numbers do not lie. Highball bouldering is the ultimate form of climbing, combining extreme difficulty with extreme danger.

I’m no mathlete but here’s how I see the graph shaking down:

Tramping

A venerable pastime, with much to recommend it. But two legs, a heavy pack and wet socks are all you need to do New Zealand’s most demanding tramps. Hazards include burning your fingers on the billy teapot, snorers and huts full of tourists. Sure, people die tramping, but then people die playing golf too.

Bouldering

Common garden variety bouldering gets to the top of the difficulty axis, but next to nowhere on the danger axis. A code in which sitting and lying-down starts are regarded as legitimate practices is always going to struggle for supremacy. Have you ever seen a picture of a boulderer unleashing the fury mere inches above the ground and thought Cripes, get down from there! No. Next.

Sport

Unlike the other codes plotted, sport climbing actually gets less dangerous as it gets more difficult. That is because the number of bolts per metre tends to increase as the grade increases. And because most people who get hurt sport climbing usually do so when they’re still learning—or when their belayer is!

Alpine

Most alpinists were probably expecting alpine climbing to top the table. There is no denying the extreme levels of danger that can be found in the mountains (if you look hard enough). The problem is that it just isn’t very difficult. Exhausting, yes. Hard, no. It’s mostly walking, sometimes scrambling, occasionally sketching. Yet blind people, old people and people with no legs can do it, all the way to the top of the earth in fact. And the ‘hard’ stuff is mostly just long, dangerous, exposed, dangerous, cold and dangerous. Ain’t no moves that your average V4 boulderer couldn’t pull. Just saying.

Ice

Climbing ice is dangerous, especially in New Zealand, where it might more accurately be described as almost-stationary-water climbing. Again, however, it just isn’t that hard. And ice climbers know it too—they even dispensed with ice tool leashes in recent times, in a vain attempt to improve their ranking. Fail. Ice is barely vertical at the best of times. And all that mixed malarkey just looks like rock climbing for people with weak fingers.

Soloing

A serious contender for the ‘ultimate’ code, but it falls short because of a lack of high-end difficulty. It may be splitting hairs but (to paraphrase Matt Pierson, writer, boulderer and bon vivant) the difference between soloing and highball bouldering is falling. When soloing, the climber does not accept the risk of a fall. With highball bouldering, that risk has to be accepted, embraced even. That is borne out in the stats: the hardest solo in New Zealand that I know of is Toby Benham’s ascent of Moment Of Greed (29), a staunch route with a crux at mid-height in the V7/V8 range and a trickyish top-out. That’s so many notches below the difficulty of the hardest highballs, it’s not even funny. Plus, you could see the harness under Toby’s trousers in the photos!

Highball

I don’t know anyone who has died highball bouldering, and I hope I never do. But it has happened. I have seen people climb boulders from which a fall would be fatal. And I’ve seen broken arms and legs. Not on goat tracks or cake walks either—on proper hard, proper high problems. I sometimes wonder if the rest of the New Zealand climbing scene has any idea about the supreme acts of skill, strength and bravery that our top highball boulderers have produced in recent years. Probably not. They probably still think climbing the Bowen-Allan Corner on Moir’s Mate is ‘badass’.

What Does It All Mean?

The earnest amongst us might well be wondering. Well, Ton Snelder once wrote of Roland Foster: ‘Foster’s achievements were little understood by the climbing community. Rock climbing was polarised from its bigger brother, mountaineering, and apart from a handful of devotees there was no recognition of his achievements. Had Foster been climbing new routes on Himalayan peaks in an equivalently up-to-date style, and if rock climbing was as respected as that noble pursuit, he may well by now have been Sir Roland.’ Foster’s bold, difficult routes inspired those words, and they are equally apt for a new generation of gung-heroes who have eschewed the ropes but not the verticality or difficulty in their search for something proud, something that will inspire fear and desire in others, something that may take only minutes or seconds to complete but which may go unrepeated for years. Some will dismiss such deeds as party tricks. As if risking life and limb on some Weet-Bix ridgeline in the Southern Alps or rolling the dice on some nearly (but not quite) vertical snow pile is more remarkable. To those people I say: think what you will, but the numbers do not lie.

Words and Images by John Palmer

This piece originally appeared in The Climber #85 (spring, 2013).