Expedition Report: England's Green And Pleasant Land

The snow has started falling again. I’m aware of a recurring theme in my writing—that whenever the weather turns bad and I’m confined to the interior of our home or a cafe, words seem to swirl around in my head until they find some sort of logical pattern that is understandable, at which point I do my best to put them onto paper before they swirl around into further irrelevance. Given our current situation, it seems like an ideal time to explain the happenings of the past week or so.

Isaac and I made the venture from LA to Manchester, enjoying the magic of three economy seats on an 11-hour flight with a stranger from Berlin. The food was incredibly questionable, the in-flight entertainment tried its best to entertain on the small format screen and sleep was something I dreamed of as I sat upright with my eyes closed for the majority of the flight.

The winters of the northern hemisphere have been unusual this year. In the Americas they’ve had an unusually warm and wet season. While in the UK they’ve had one of their driest years, which lucky for us has meant that, of the past six days we’ve been in Sheffield, we’ve been able to climb on four of them.

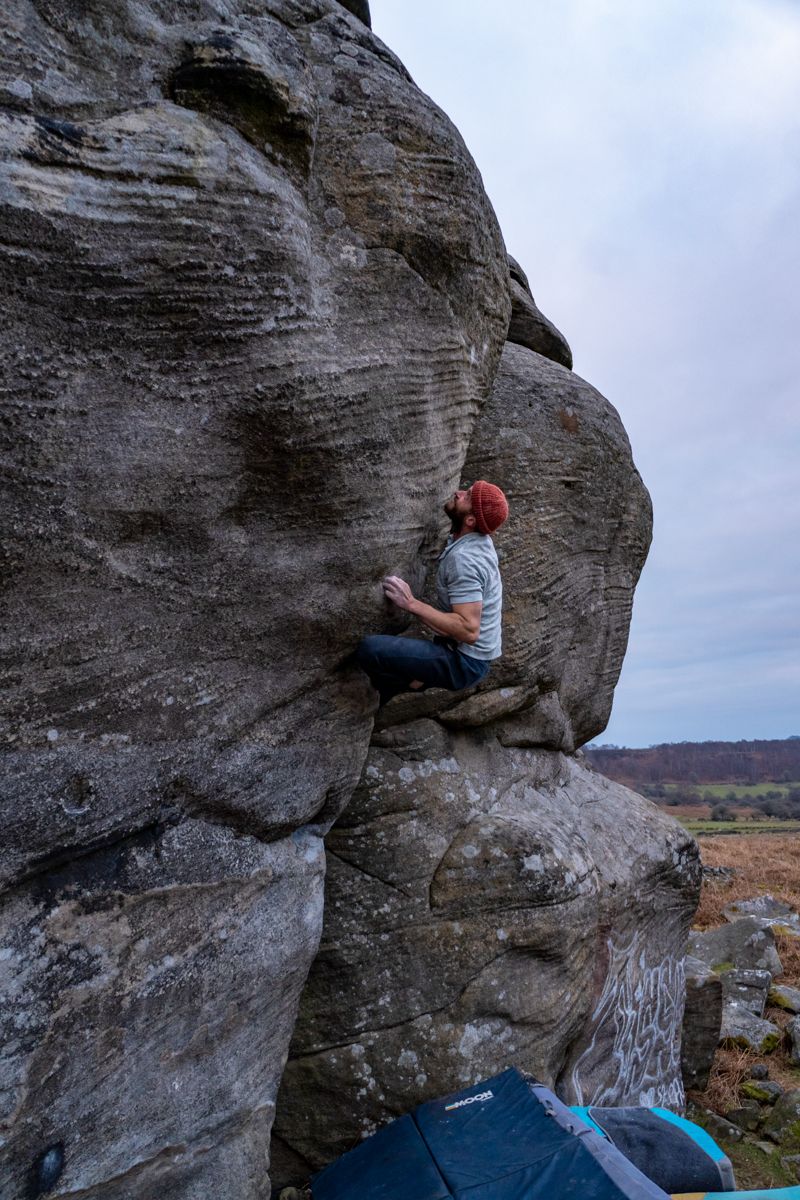

Compared to American vistas, the beauty of the Peak District is more subtle, but no less deserving of the term. Over the previous months, we observed searing mountains and far off horizons, here we enjoy the scenes of rotund, introverted hills with stone walls creating patchwork fields, deciduous trees clump together around quaint stone villages in the bottom of open valleys. It’s an understated beauty, but in some ways I find it more appealing. Without the confines of mountain ranges, the weather rolls in and out as it pleases. The clouds distribute themselves evenly across the expanse, allowing for crepuscular rays to beam through to the hazy underlayer. Our local climbing friends seem to pass this off, paying little attention. Perhaps the novelty has worn off for them—the frequency of its occurrence making it less worth noting. I can’t seem to look away, this new landscape is captivating.

Between these moments of appreciating the landscape we did some incredible climbing. The nature of the rock here creates these features and forms, which quite like the undulations and bulges of Castle Hill, dictate that the body must move around them rather than just pull between micro features. This lends itself to a wonderful style of climbing, which is far closer to a dance than to an exercise in strength. At Stanage Plantation, on our first day in the Peak, we tasted only a small portion of the possibilities for this style of climbing at the lower grade level. It was obvious to see that it could be taken further to bolder lines, rounder arêtes, and smearier feet—a delightful combination of variables.

The following days allowed us to sample some of the quality hard grit blocks and experience our first taste of UK trad: headpointing Kaluza Klein (E7 6c). After rehearsing the moves on a top rope, Isaac and I decided it was a better approach to just boulder the route rather than tie in, as the fall from the upper moves would be poor, with or without a rope. The climb follows a beautiful rounded arête with horizontal breaks (a comically common occurrence in these parts) culminating in a one-handed slap up to the top out jug, with the potential to be off balance if done incorrectly. The experience of top roping, making safe, rationalising actual risk and finally doing the line was indescribably rewarding. It had been too long since I’d had that approach to climbing and it was a reunion I was grateful to have. The possible challenges awaiting in this style on the gritstone is an exciting prospect.

It's interesting to note that for my personal climbing experience on this holiday, the styles of climbing that I enjoy most are the ones I could compare to home. I cared little for fist crimping on overhangs or steep hand jamming—although I enjoyed some time in the genre, I tired of it quickly and longed for something that related to what I was used to at the Hill (it's important to mention that the rest of the sub-alpine team took to these styles with much gusto). This may seem like a missed opportunity on my part, to delve completely into styles which I would not be able to experience in Aotearoa. I would have to agree. But the pleasure I would get from climbing a slab or quirky technical climb would be far greater than forcing it on these more foreign styles, and I couldn’t deny myself that satisfaction. On the gritstone, there is an incredible amount of pleasure from body movement on rock. I am extremely thankful that there is other climbing in this world which requires a similar set of skills to that in Castle Hill. Although the exact subtleties are different—there are less high foot ‘hip-overs’ and less heels down—there is a unique style here which is yet to be unlocked. ‘Cheaty little moves’ seem common, where you put faith in a foot or a hold and engage momentum to make it to the next secure body position. This style, as of this moment, is not fully understood—but we are well on the way to figuring it out.

When I started writing this specific report the snow which had fallen overnight wouldn't have reached over the soles of my shoes. As I look out the window now, I see a foot of snow across the driveway and the possibility of climbing outdoors over the next few days seems unlikely at best. Sheffield has stopped working momentarily while they deal with the inconvenience of frozen moisture all over their roads. Given that the whole of yesterday was spent in the confines of a single room, today Isaac and I were keen to escape the house no matter how wet and cold our feet got.

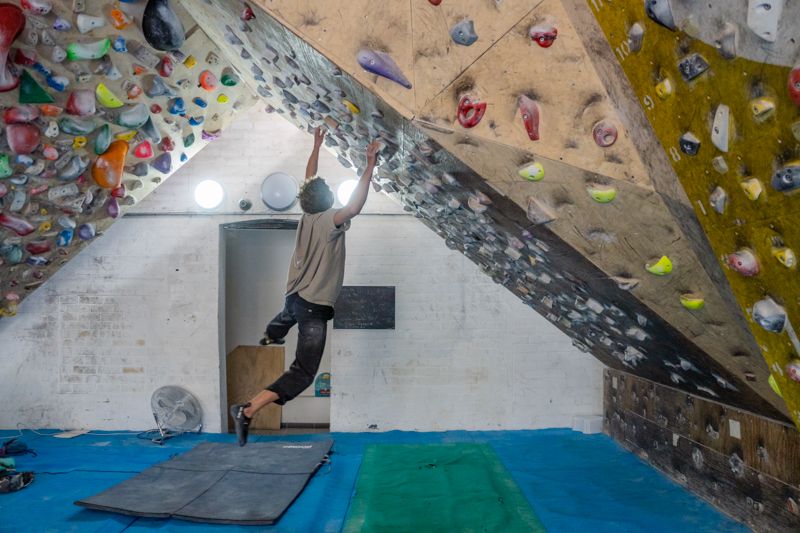

There is a rich history of climbing in this city, which at times I feel is a peculiar point of interest—the decisions and actions of people 30 years ago entertaining our imaginations in the present day. However, it has an undeniable alluring quality to it. One specific area where this allure is situated is the School Room, a small training facility which hosts one of the original training boards that are so common today. This, like the problems and lines on actual rock nearby, was one of the things we were most keen to see on this trip.

Our approach to the School Room, given that the roads were not really functional, was a 50 minute walk down into the heart of Sheffield. Walking through a city, when compared to driving, gives you greater time to take in your surroundings. This walk, as we discussed along our journey, was beautiful. But why exactly it was beautiful we couldn't quite pin. Neither myself nor Isaac enjoy the occurrence of snow, it is an inconvenience unmatched with any other common weather event, yet we cannot deny its inherent beauty. We speculated across this journey that it was the novelty that made it beautiful, the fact that it was not a regular occurrence, quite like a model with peculiar features—wide set eyes, exaggerated jaw line, pronounced cheekbones. The issue with this explanation though, is that not all humans with irregular features are beautiful, there are definitely people out there with irregular features who I would not be able to say are visually beautiful. Therefore, we could not say that the frequency of snow’s occurrence was the sole reason for it to be deemed beautiful.

We theorised that it perhaps be then the forms that fallen snow takes on the landscape. How it softens the world it lies on, transforming sharp angles into smooth curves. I agree that this could lead to the scenes we walked past being called beautiful, the rounded off roofs overhanging with snow and the walls with hats that sat atop them, I would call them beautiful, but again I don't think that it makes it any more beautiful than those objects previously were. The houses the snow sat upon would still be beautiful on a summer’s evening, as would the stone walls with their cracks and gaps brimming with dense moss.

I think one of the main reasons why I find this incredibly inconvenient occurrence beautiful is how light interacts with it. How the sun catches random snowflakes, refracting light in the moisture and giving the appearance of a sparkling surface. How those rounded features that I mentioned in the previous paragraph, make the slow, diffused transition from the shaded face of a surface to the sunlit side. So, the question arises then if the beauty that we’re a witness to is the snow or the light’s effects on the snow.

We discussed in further depth if the beauty that we acknowledge in all objects was in fact light interacting with the surface of those objects and not actually the objects themselves. The exact specifics of that discussion no longer seem relevant to our story of our journey to the School Room and so I’ll end this paragraph here.

This topic of conversation entertained us for the majority of our wander into town, and although we may not have answered it, it allowed us to appreciate what we were viewing more than if we hadn't mentioned it. There is a simple freedom in unquestioningly appreciating things, but there is also a rewarding satisfaction to figuring out what you enjoy and why. It's having the balance of both approaches which I think is important.

The School Room, in its current state, is a single 8m by 20m room with a window-wall at one end and a bathroom at the other. The spaces in between on either side are lined with steep walls of ply littered with small resin and wooden holds. The facility is not designed for introductory climbers, this is specifically built for training at a level that we don't have much of in New Zealand. Our friend, mentor and guide Dave Mason was coaching some local hard-bods in exercises revolving around lifting ungodly amounts of heavy metal strapped around their waist as they hung off a small piece of wood screwed to the wall. We left them to it and headed over to the original board to begin our touristic appreciation.

With the slick, modern state of climbing globally, the walls and holds that you will frequently see in gyms are clean, ergonomic and aesthetic. The holds on this wall are novel. There are weathered, wooden bannisters that were salvaged from a skip—having obviously been exposed to rain and some frost—while the resin holds that are on there, I'm sure at one point in time would have had specific colours that you could differentiate them by, now are all a very similar shade of grey. Describing the wall, it doesn't sound like the makings of a good climbing wall, but I would go as far as saying it's the best indoor climbing I've done in years.

When it came to climbing, we performed as expected, below our outdoor level. We thrutched our way through a handful of mid-range climbs and thought it was about time to try some upper end classics. At this point the hard-bods that were dangling strengthily when we walked in joined us and went about clearly displaying the gap between the level of climbing in New Zealand and the level in the UK. On multiple occasions, those little men did moves that would require Isaac and I to control our fits of laughter and subsequently pick our jaws up off the floor. They were comfortable on the board, to say the least, and it was a pleasure to witness. Our performance wasn't quite as impressive, we managed some close to limit ascents of classic climbs first done in the ‘90s, which were literally the warm ups for these wads (UK slang for strongman). Even so, at the end of the session there was an odd satisfaction, comparable to the feeling of having climbed outdoors.

With the weather deteriorating to a constant bleakness, what's left of the sub-alpine team, along with honorary member Dave, have driven, caught a ferry and driven some more to reach the bouldering mecca of Fontainebleau, France. We’re here for a month, the sky is currently blue and it looks to be that way for a while. Long may that last.

-By Matt Corbishley

Additional photography by Sam Pratt