Rock Shoes 201

Following up from the introductory article Rock Shoes 101, today I’ll discuss the idea of a ‘shoe quiver’, run through some of the major brands and offer a few other reviews of specific shoe models. First, let’s dive into the quiver concept.

When reading the manufacturer-provided information for any particular model of rock shoe, you’ll come across text like this: ‘… ideal for top performance both on rock walls and in the gym, designed for use on overhangs and slabs.’ Much like almost every mountain bike is described by its manufacturer as ‘light and nimble on technical climbs, but also stable and assured on fast, technical descents.’ Or, any given pair of skis will have the properties of delivering ‘superb edge hold for carving on icy groomers, with excellent float in powder and pivotability off piste.’ Yeah, right.

The truth is that in the majority of cases the properties that make a rock shoe good on lower-angled climbing are in direct opposition to the properties that would make it good for steep climbing. Just like a mountain bike with a long wheelbase and a large range of suspension travel is built for the downhill and clearly going to sacrifice uphill performance; or a pair of 88mm underfoot, heavy and stiff skis are going to excel at speed on groomers and be fairly debilitating in soft, deep snow. You can’t have it all.

This isn’t to say that capable all-rounders don’t exist in any of these areas, but as everyone knows—the jack of all trades is the master of none. If you want the best performance, you want to go with a shoe that has the design intent of being made specifically for the style of climbing at hand. An experienced and skilful climber will be able to use a pair of all around shoes on any terrain and get away with it, but they will do better in a more specific pair. More crucially, an intermediate climber might develop worse footwork when learning to use their feet on different angles of terrain if they are in inappropriate shoes.

My advice is that anyone who likes to climb on a range of different angles will likely benefit from owning a ‘quiver’ of at least two different pairs of rock shoes. The basic quiver would be a relatively stiff, flat profiled shoe for use on face climbing terrain where edging and smearing are required, as well as a much softer down-turned shoe that can be used on steep terrain. If you do a lot of low-angled smearing, such as moderate boulders at Castle Hill, you might want to make the flat shoe softer and potentially make it a velcro model for easy on and off. If you don’t boulder much and tend to spend more time climbing face routes, then you might want a bit more support from a stiffer shoe and consider a lace-up or velcro shoe that offers more precise fit adjustment. For the down-turned shoe, the more your steep climbing happens indoors versus outdoors, the softer I’d be tempted to go—as pliability on large volumes and for smedging on slick jibs in the gyms is very useful. But a super soft shoe is still useful outdoors a lot of the time—so long as the steep terrain is relentlessly steep and so tends to have large or non-positive footholds (like the Cave). If your steep climbing still requires putting a lot of power through edges on a headwall or involves a lot of small but positive footholds, a downturned shoe with a bit of toe support (like the La Sportiva Solution) might be better than a very soft shoe (like the Scarpa Drago or Unparalled Leopard II, or whatever other shoe you are distracting yourself with while you wait for Adidas/Five Ten to bring back the Team).

My advice is that anyone who likes to climb on a range of different angles will likely benefit from owning a ‘quiver’ of at least two different pairs of rock shoes. The basic quiver would be a relatively stiff, flat profiled shoe for use on face climbing terrain where edging and smearing are required, as well as a much softer down-turned shoe that can be used on steep terrain. If you do a lot of low-angled smearing, such as moderate boulders at Castle Hill, you might want to make the flat shoe softer and potentially make it a velcro model for easy on and off. If you don’t boulder much and tend to spend more time climbing face routes, then you might want a bit more support from a stiffer shoe and consider a lace-up or velcro shoe that offers more precise fit adjustment. For the down-turned shoe, the more your steep climbing happens indoors versus outdoors, the softer I’d be tempted to go—as pliability on large volumes and for smedging on slick jibs in the gyms is very useful. But a super soft shoe is still useful outdoors a lot of the time—so long as the steep terrain is relentlessly steep and so tends to have large or non-positive footholds (like the Cave). If your steep climbing still requires putting a lot of power through edges on a headwall or involves a lot of small but positive footholds, a downturned shoe with a bit of toe support (like the La Sportiva Solution) might be better than a very soft shoe (like the Scarpa Drago or Unparalled Leopard II, or whatever other shoe you are distracting yourself with while you wait for Adidas/Five Ten to bring back the Team).

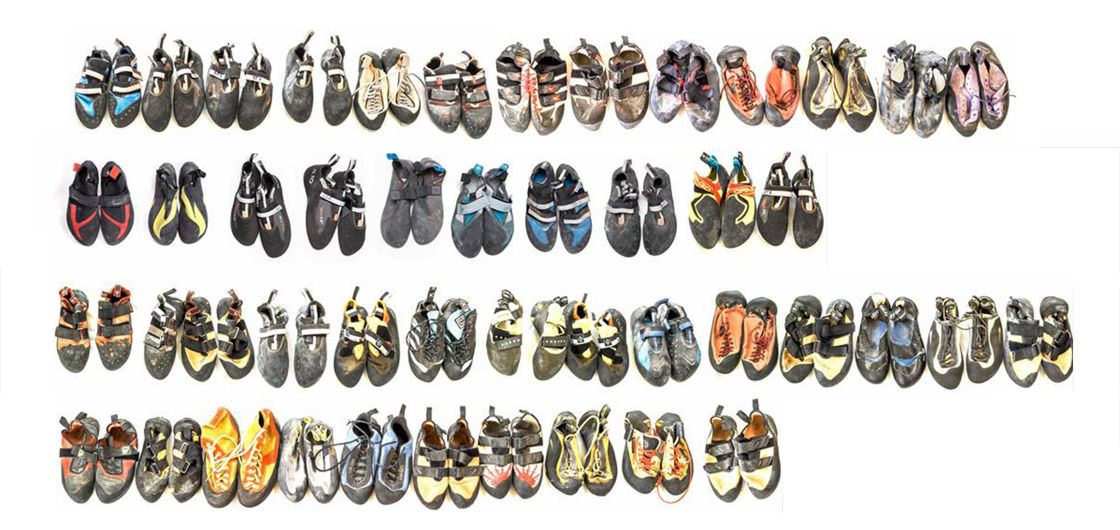

This is the basic idea behind the shoe quiver. Do you need a quiver of more than two? Well, that depends on just how much of a climbing nerd you are (and how much you are willing to spend). As you can see from the image above of Derek Thatcher’s shoe collection, the more you’re prepared to explore different performance characteristics and how they work on different types of stone and shapes of foothold, the more shoes you’ll be tempted to end up with.

Personally, I tend to actively use four pairs. These are a very soft downturned shoe for steep climbs (Five Ten Team/La Sportiva Theory), an edging-biased all-round pair with a very mild downturn for steep face climbing (Five Ten Quantum lace) and a slightly less tight, flatter-profiled shoe that I would swap out to from the previous as the face climbing gets less steep and also use for longer multi-pitch outings (Five Ten Pink Anasazi lace or Verdon lace). As I don’t like to wear my good shoes indoors, I have a sacrificial indoor pair that is usually a well-worn in pair of the steep soft shoe example (currently a La Sportiva Python). Climbing indoors involves a lot of time standing on carpet and polished/caked-in-chalk holds which tends to cause the sole rubber to glaze over with time and lose some tack. You can restore this with a bit of sanding/grinding of the sole, but I’d rather just wear an old pair. Which brings me to the other part of the quiver, and that is age cycling of shoes.

Personally, I tend to actively use four pairs. These are a very soft downturned shoe for steep climbs (Five Ten Team/La Sportiva Theory), an edging-biased all-round pair with a very mild downturn for steep face climbing (Five Ten Quantum lace) and a slightly less tight, flatter-profiled shoe that I would swap out to from the previous as the face climbing gets less steep and also use for longer multi-pitch outings (Five Ten Pink Anasazi lace or Verdon lace). As I don’t like to wear my good shoes indoors, I have a sacrificial indoor pair that is usually a well-worn in pair of the steep soft shoe example (currently a La Sportiva Python). Climbing indoors involves a lot of time standing on carpet and polished/caked-in-chalk holds which tends to cause the sole rubber to glaze over with time and lose some tack. You can restore this with a bit of sanding/grinding of the sole, but I’d rather just wear an old pair. Which brings me to the other part of the quiver, and that is age cycling of shoes.

The performance of a pair of climbing shoes will change over the life of the shoes. This aspect has been much improved by more recent designs. A shift to synthetic textiles for the shoe uppers has reduced the amount of stretch over prolonged use versus an unlined leather shoe. Unlined leather shoes tend to stretch and bag-out, at some point losing the supportive snugness they had earlier in their life. This is partly why—going back a few decades—everyone used to size their shoes ridiculously tight when new, because they would eventually stretch to a volume that was suitable for climbing in. As climbing shoe design has got better, this is no longer necessary and a pair of shoes that are overly tight when new are unlikely to ever be a great fit for climbing.

Likewise, the technology in the mid soles has greatly improved. The earliest models of climbing boots were board lasted, making them as stiff as the rigid mountain boots specific rock climbing footwear evolved from. These were great for feeling nothing while standing on tiny edges on the faces and slabs of the day, but essentially useless for anything else. Climbers at the time would take hammers to new pairs of shoes to smash the midsoles into some sense of pliability so they could smear and have some sensitivity on footholds.

Thankfully, those days are gone and the evolution of design and materials used in rock shoes means you can now use a pair with minimal wear-in process and get consistent performance for the majority of the lifetime of the shoe. Despite this, the performance characteristics will change as the shoe wears and the sole becomes thinner, generally making shoes softer and make them feel more sloppy. For a softer, down-turned shoe, you may lose a small amount of precision, but the key performance aspects of the shoe aren’t really compromised. But for the stiffer, flatter shoes you are likely to slowly lose the pure edging power that you want in that shoe and by the end of its lifespan it is probably better to relegate it to the smearing, lower-angled terrain category. For me, this generally means I will start wearing in a new edging pair when the previous pair is more than halfway through its life cycle, or whenever I start to notice any slight decrease in performance. This tactic means that buying a new pair of shoes specifically for that second tier of use is not necessarily required.

Looking after your shoes

I often see people walking around in the dirt and mud at the base of the crag in their rock shoes. Not only does this contribute to wearing out your shoes, it also causes the rubber to lose its tack. Brand new shoes have a finely ground surface and a non-reflective matt look to them. If your shoes have a smooth, reflective or glazed look to the rubber, they will have lost some stickiness. You should keep the soles of your shoes as clean as possible at all times in order to get the best performance from the rubber. This might extend to a spit polish every now and then. Walking around in the mud and then climbing on the rock also tracks dirt onto the footholds of the climb and contributes to rapid polishing, especially in places with soft stone like Castle Hill Basin. Care for your shoes, care for the rock.

People generally avoid washing leather shoes for fear of them changing size. If your feet sweat, or you walk around in the mud in bare feet and then put your shoes on to climb, you will probably find your shoes start to smell at some point. If that bothers you (or if you are concerned that it might bother others nearby ;-) ), you can wash synthetic shoes with no risk as to compromising their fit or performance.

Resoling

Is it more environmentally-friendly to get your shoes resoled, rather than just chucking them and buying another pair when the rubber under the toe wears through? Yes.

Will they perform just like new? No, unfortunately not.

If your shoe uppers are still in excellent condition and haven’t stretched out too much and there isn’t significant wear on the toe rand, then a resole could well be worthwhile. If the toe rand or uppers are worn, they will likely blow out before you have got your money’s worth from the resole and the ‘toe caps’ some resolers offer for rand repairs are a bit of a lottery in my experience.

A new sole of thick rubber will initially give the shoe back a bit more stiffness, but it will likely remain softer than when new and continue to soften. This can still mean the shoe is useful, especially for smearing on lower-angled terrain and for extended use on long climbs when comfort starts to play more of a factor. But you probably only need one shoe like this, and it will likely last a while, so getting all your shoes resoled every time is probably not worthwhile. As stated above, some types of shoe are better suited to this category than others.

Major Brands:

Scarpa

Scarpa are an Italian brand with a storied history in making mountain boots, ski boots and rock shoes. They make quality shoes in a good range of styles and use Vibram rubber soles. Historically, Scarpa have been particularly popular in the UK, but not that easy to come by in New Zealand. This has now changed with Southern Approach bringing in the Scarpa range, granting sponsorship to some young local climbers and holding stock in Bivouac stores—so you can try them on!

Scarpa are an Italian brand with a storied history in making mountain boots, ski boots and rock shoes. They make quality shoes in a good range of styles and use Vibram rubber soles. Historically, Scarpa have been particularly popular in the UK, but not that easy to come by in New Zealand. This has now changed with Southern Approach bringing in the Scarpa range, granting sponsorship to some young local climbers and holding stock in Bivouac stores—so you can try them on!

The default sizing is in euro sizes and you would usually down size 2-3 sizes from your everyday street shoe size. I am a 48 street shoe and usually don’t quite fit into a 45 in Scarpa (which is often the largest size they make).

La Sportiva

La Sportiva are the other big Italian brand and have a strong historical following in New Zealand. Their mountaineering boots such as the Nepal EVO are of unsurpassed popularity, they also make trail running shoes, ski boots, skis and a range of clothing. They support many of the world’s very best and most famous rock climbers, such as Adam Ondra, Tommy Caldwell, Alex Honnold, Julia Chanourdie and Barbara Zangerl. La Sportiva make a very large range of shoes and have a specific model for any conceivable purpose, from the big wall specialist TC Pro through to shoes designed specifically for indoor bouldering competitions. They have become known in recent decades for taking an innovative approach to design and are probably the industry leaders in terms of both innovation and build quality. Like Scarpa, they use Vibram rubber soles.

The default sizing is in euro sizes and you would usually down size 2-3 sizes from your everyday street shoe size. I am a 48 street shoe and usually wear a 45 or 46 in La Sportiva models (previously a 45 but more recently a 46 as their sizing range has expanded).

Five Ten/Adidas

Five Ten originated out of California, USA as the brainchild of Charles Cole. Historically they have been known for their innovative designs and generous range of shoes, as well as their secret formula Stealth C4 rubber. Twenty years ago, the majority of top climbers seemed to wear one or the other Anasazi model (Velcro or pink lace) and swear by the superior rubber performance. These climbers (and many others) often mis-pronounced Anasazi with a ’t’ in it, maybe because they felt like ‘stars’ in the shoes. Unfortunately, Five Ten have also been known for inconsistent sizing and poor build quality, as well as a propensity for discontinuing extremely popular models. Their range of mountain biking shoes is equally as famous as their rock shoes.

The Five Ten brand is still alive, but after the company was purchased by Adidas some time ago the branding has slowly evolved, as well as moving production from the US to Asia. Some hoped that these changes might bring a bit of stability to the quality control and sizing of Five Ten’s rock shoes, but I’m not convinced there has been a significant improvement yet. As production has changed, we’ve seen a temporary decrease in the range of models made and general availability of Five Ten shoes, but that seems to have passed now. They still seem to have an annoying strategy of discontinuing tried and trusted models like the Team and bringing out ‘new’ models in their place (like the Hiangle Pro, do we want a ‘Pro’ version of the Hiangle, when a Team already does everything that shoe is supposed to do so well?).

Unlike the brands above, Five Ten shoes are usually the same as your street shoe size (default sizing is US, I wear a US13.5). While on paper this makes sizing much simpler, in reality the experience of many people is that two Five Ten shoes with the same size marked on them can be up to 1.5 sizes bigger or smaller.

Unparallel Sports

Unparallel Sports was started by a group of former Five Ten employees when the original company was sold to Adidas. The rumour is that they took a selection of Five Ten’s best lasts and the secret rubber formula with them. They are currently trying to sit in the same place in the market that Five Ten used to own, making high performance rock shoes and mountain biking footwear. Some of Unparallel’s early models even cheekily referenced which former Five Ten shoe it was a copy of, though they now seem to have progressed beyond that stage and are making unique new shoe designs also.

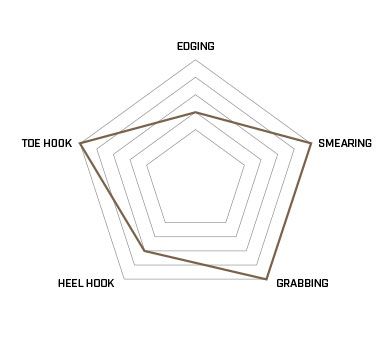

As a climbing shoe nerd, I like the amount of information Unparallel supply on their website, giving detailed information about the different rubber used in different shoes and on different parts of the shoe, and also a visualisation of the design intent of the shoe. This five pointed diagram lists the not-quite-mutually-exclusive properties of edging, grabbing, smearing, heel hooking and toe hooking and marks an internal shape that corresponds to the shoe’s performance in each aspect. This honesty is refreshing in recognising that a shoe won’t be amazing at all of those things, though admittedly their ’Flagship’ model is shown to be near to maxing out in all five categories! Maybe it is just that good?

As a climbing shoe nerd, I like the amount of information Unparallel supply on their website, giving detailed information about the different rubber used in different shoes and on different parts of the shoe, and also a visualisation of the design intent of the shoe. This five pointed diagram lists the not-quite-mutually-exclusive properties of edging, grabbing, smearing, heel hooking and toe hooking and marks an internal shape that corresponds to the shoe’s performance in each aspect. This honesty is refreshing in recognising that a shoe won’t be amazing at all of those things, though admittedly their ’Flagship’ model is shown to be near to maxing out in all five categories! Maybe it is just that good?

I haven’t yet owned a pair of Unparallel shoes, mostly because initially their sizing was quite limited, though they now seem to make most models up to a US14. My understanding is that the sizing remains similar to Five Ten (street shoe size).

Boreal

Boreal used to be a major player in rock shoes and were a leading innovator in the early days of sticky rubber. Unfortunately, they have slipped behind the rest of the pack and have limited global popularity outside of Spain. They use a proprietary rubber called Zenith. No longer widely available in New Zealand.

Ocun

Ocun (pronounced something more like ‘oxen’ than ‘oh-coon’) are a Czech manufacturer of climbing equipment. They are a relative new player in climbing shoes, but have achieved quite a lot of traction in the industry with some eye-catching designs. They were distributed in New Zealand until recently, but are now harder to come by.

Their website provides quite detailed information in terms of last widths, different rubber and midsoles stiffnesses and profiles across their range.

Red Chilli

Red Chilli were relatively popular in the late-nineties and early-noughties but now seem to have been relegated back to a second tier brand. Their initial marketing had a bit more sex-appeal and the brand was fronted by ‘90s hero Stefan Glowacz who exuded a cool, European arrogance. I had one pair of their shoes once and they were an awful fit. I admit I don’t know much about their current range and that might be because when I looked at their website I didn’t recognise a single name amongst their team of sponsored athletes. They are available in New Zealand in a limited range.

Red Chilli were relatively popular in the late-nineties and early-noughties but now seem to have been relegated back to a second tier brand. Their initial marketing had a bit more sex-appeal and the brand was fronted by ‘90s hero Stefan Glowacz who exuded a cool, European arrogance. I had one pair of their shoes once and they were an awful fit. I admit I don’t know much about their current range and that might be because when I looked at their website I didn’t recognise a single name amongst their team of sponsored athletes. They are available in New Zealand in a limited range.

Black Diamond

BD are one of the world’s most trusted brands when it comes to technical climbing equipment, as well as making backcountry ski gear. They have more recently really pushed into the clothing side of things. The rock shoe range is pretty new, but slowly gaining traction and are available here in New Zealand if you want to try some on in the shop. I haven’t tried a pair as their sizing doesn’t quite stretch to the sasquatch range.

BD are one of the world’s most trusted brands when it comes to technical climbing equipment, as well as making backcountry ski gear. They have more recently really pushed into the clothing side of things. The rock shoe range is pretty new, but slowly gaining traction and are available here in New Zealand if you want to try some on in the shop. I haven’t tried a pair as their sizing doesn’t quite stretch to the sasquatch range.

Tenaya

Tenaya emerged from Spain in the late ‘90s and their early marketing suggested they made shoes very similar to Five Ten but with better build quality and lower prices. They use Vibram rubber soles. I’ve always enjoyed the visual design of their shoes but haven’t owned a pair myself. They supply some of the world’s very best climbers with shoes (and presumably money), such as Alex Megos, Jimmy Webb, Chris Sharma and Josune Berziartu. Tenaya shoes are not available in New Zealand stores.

Evolv

Evolv made a big splash when they first emerged on the scene supporting Chris Sharma around the time he climbed Es Pontas (they even named a shoe after it). While Sharma is no longer on board, they still sponsor a range of the very best climbers out there, including Dai Koyamada, Daniel Woods and Ashima Shiraishi. They use a proprietary Trax rubber. I’ve never owned a pair of Evolv shoes, but I did once hike halfway across Los Angeles with John Palmer trying to find some Five Tens to try on. We ended up only finding Evolvs and John bought a pair in an attempt to salvage something from the experience. He did not like them. Evolv shoes are not widely available in New Zealand.

So iLL

Straight out of South Illinois with a funky urban attitude, So iLL originally emerged as a maker of holds but have since pivoted to also make climbing shoes. They appear to use Unparallel’s rubbers on their shoes, though the information their website provides is rather patchy. Their shoes are made in the USA. It is hard not to draw the conclusion that they are a style over substance brand, but maybe that is me jumping to conclusions from the fact that they offer a Momoa Pro model. La Sportiva have the Tommy Caldwell pro model, Unparallel have the Tomoa Narasaki pro model, very different climbers, but both people I can get behind designing a pro model shoe. A Jason Momoa pro model seems a bit of a stretch. Their designs are quite eye-catching, but I have very limited experience of their performance as I don’t think anybody I know has ever owned a pair. But they have recently become available in New Zealand, so maybe that will change soon.

Straight out of South Illinois with a funky urban attitude, So iLL originally emerged as a maker of holds but have since pivoted to also make climbing shoes. They appear to use Unparallel’s rubbers on their shoes, though the information their website provides is rather patchy. Their shoes are made in the USA. It is hard not to draw the conclusion that they are a style over substance brand, but maybe that is me jumping to conclusions from the fact that they offer a Momoa Pro model. La Sportiva have the Tommy Caldwell pro model, Unparallel have the Tomoa Narasaki pro model, very different climbers, but both people I can get behind designing a pro model shoe. A Jason Momoa pro model seems a bit of a stretch. Their designs are quite eye-catching, but I have very limited experience of their performance as I don’t think anybody I know has ever owned a pair. But they have recently become available in New Zealand, so maybe that will change soon.

Saltic

Saltic are another Czech shoe maker with a range of lively-looking designs. They are available in New Zealand through Aspiring Safety. I had a pair as my first ever pair of rock shoes twenty years ago, but haven’t tried them recently. I remember the move from my Saltics to a pair of La Sportiva Cobras as fairly revelatory, but that was likely as much to do with fit as anything. They use a proprietary Extasy rubber.

-Tom Hoyle

Guest Reviews:

Five Ten Team - Erica Gatland

I have been climbing since I was ten years old, and I don’t think my feet have grown since! When your feet are a women’s size five, and you wear your climbing shoes two sizes too small, it is very hard to find a shop in New Zealand that will stock your size (almost impossible) and you are forced to buy them online with the risk of ordering the wrong size or fit and spending hundreds on shipping. When I find a shoe that works for me, I stick with that pretty much until they stop making them anymore …

I have been climbing since I was ten years old, and I don’t think my feet have grown since! When your feet are a women’s size five, and you wear your climbing shoes two sizes too small, it is very hard to find a shop in New Zealand that will stock your size (almost impossible) and you are forced to buy them online with the risk of ordering the wrong size or fit and spending hundreds on shipping. When I find a shoe that works for me, I stick with that pretty much until they stop making them anymore …

I prefer a soft shoe as I find stiff shoes very hard to break in as I only weigh 50kg. Also, the shoe is never quite the same when it is shrunk down to a children’s-sized foot. All the proportions are slightly off, however the rubber thickness remains the same and what would normally be a moderately stiff shoe becomes like wearing bricks on your feet, while what would normally be a very soft shoe is more like a 'normal' stiffness. However, the best thing about weighing nothing and having tiny feet is that you don’t seem to wear through shoes as quickly, my shoes will last me years!

Currently, I am on my last pair of Five Ten Teams (they are no longer made) which have been my favourite shoe to date. The Teams are a soft, downturned slipper which are great for all terrain and although they are quite aggressive, they are still great for smearing. They are broken in right out of the box, super comfortable and very high performing. These shoes have gotten me up some of my hardest boulder sends, sport routes and put me on top of the podium in many competitions. The only time they have let me down is when you have to really edge on tiny footholds, that’s when I swap them out for my other pair of Five Tens, the Anasazis. I have pretty much only ever climbed in Five Ten shoes, the rubber is far superior to any other rock shoe and really is the only solution for pushing your limits on smooth limestone slabs in 'The Basin'.

Tenaya Oasi LV - Graham Johnson

The Oasi, and it's sibling—the Oasi LV—are top end shoes designed for vertical to overhanging sport climbs and bouldering. For those not familiar, Tenaya is a Spanish shoe company whose products can be seen on the feet of some of the best climbers in the world. However, the fact that someone sent 9a in a pair of Oasis doesn't really mean anything to this ‘mid-twenties on a good day’ climber. What does mean a lot to me is the comfort that is found in such high performance shoes. Comfort and performance have been the driving forces at Tenaya and they certainly deliver.

The Oasi, and it's sibling—the Oasi LV—are top end shoes designed for vertical to overhanging sport climbs and bouldering. For those not familiar, Tenaya is a Spanish shoe company whose products can be seen on the feet of some of the best climbers in the world. However, the fact that someone sent 9a in a pair of Oasis doesn't really mean anything to this ‘mid-twenties on a good day’ climber. What does mean a lot to me is the comfort that is found in such high performance shoes. Comfort and performance have been the driving forces at Tenaya and they certainly deliver.

The Oasi has been around since at least 2014, when it won Climbing Magazine's Shoe of the Year Award and the LV (Low Volume) was introduced a few years ago. I like that Tenaya called them ‘LV’ and put them in a gender-neutral colour to encourage people to chose the shoe that fit best, not the ‘men’s’ or ‘women’s’ versions (although the website makes reference to designing them around a woman's foot). As someone with a pretty low volume foot, I appreciate that. I can't say my male foot has had any issues. Other than the last and some slight differences in the velcro closure, the Oasi and Oasi LV are the same shoe. They use 3.5mm of Vibram XS Grip—the same rubber used in many other high-end shoes.

Colours and labels aside, this is a very comfortable, high performance shoe. I never feel like I need to rip them off after a pitch, but my feet feel perfectly snug with excellent sensitivity for vertical and overhanging routes. Not nearly as stiff as their siblings the lace-up Tarifa, the Oasi blends sensitivity with enough support to get you up most any sport climb—but I wouldn't want to stand on micro edges for hours on end in them. I'm not hard enough for toe-scumming/hooking, but there is a handy patch of toe rubber for this. While I have used them for slab and trad climbing—I've even crack climbed in them ( not recommended) and they worked—but being fitted for sport performance with slightly curled toes it was very uncomfortable. In my defence, I didn't realise my partner was dead-set on some cracks and I'd only brought the Oasis. The lycra-like tongue gives a good sock-like fit without any bunching, however I often struggle with getting my foot into them. The (on the LV) single velcro tab effectively pulls two micro adjustable straps snug with one easy motion giving good support. The regular volume version has two separate velcro tabs but effectively the same closure. I have found that if you crank them too tight the slip-lock buckles will slip a bit, which is a little annoying.

These are probably the best shoes I've had for sport climbing and they hold their own bouldering . Despite being a very similar shape and design to the Tarifa, this is not simply a ‘velcro version’ of the much stiffer Tarifa. I'd happily wear these from Castle Hill to Paines Ford.