Rock Climbing's Weighty Issue

This article was published in the spring 2023 issue of the New Zealand Alpine Journal and is republished here to reach a wider audience, especially those younger climbers who may not have a subscription to the NZAJ: Climbing In Aotearoa. Warning: this article contains many words and only climbing pictures of the author, so as not to unintentionally portray opinions of the skill or weight of any other climber.

By Tom Hoyle

The pages of this journal are testament to the multitudes of challenges and possibilities in climbing. Yet, within these broad possibilities, many climbers approach rock climbing with a purely performance-oriented mindset. They want to climb as ‘hard’ as they can. Why? Climbing hard is cool and supposedly makes you a hit with whatever type of person you want to be a hit with at parties. Climbing hard could mean V1000 boulder problems, sport climbs so long and overhanging that you need to swap ropes part way up, or vomit-inducing trad climbs involving horizontal jamming akin to wrestling a grizzly bear. Despite the varying approaches, there’s one thing performance-oriented climbers are all obsessed with—and that’s numbers.

As climbing has grown as a ‘sport’, it is becoming obvious that an obsession with numbers can be toxic to our own well-being as climbers. In climbing, there are two particular sets of numbers that form an axis of evil: grades and weight. Grade chat is perennial (yawn). But weight chat—at least in relation to ourselves—is rarely discussed. Few performance-oriented rock climbers openly talk about what they weigh, how much they want to weigh, and how they think it contributes to their performance on the rock. It’s a problem and it is making people unwell.

Weight

I like to tell my friends that ‘I have a special relationship with gravity’. It holds on to me, dearly. It refuses to let go. I simply don’t have the same frame as an elite rock climber and at 88kg I weigh at least 10—15kg more than the people I’m climbing with. I have put a considerable amount of time in my adult life into climbing as hard as I can, but I have also remained the same weight for the last twenty years, give or take 2–3 kilos. It might be my metabolism, or my zero tolerance for being hungry, but I’ve never been on the ‘drop weight to perform better’ bandwagon. I climb a few grades lower than most of my friends, more than a few lower than some of them. But I’m a handy belayer (lots of ballast) and, as a coping mechanism, I joke about how being under 85 kilograms is cheating … it’s fine.

Don’t get me wrong, if I could somehow magically be 15kg lighter and not any weaker, I would undoubtedly climb bigger numbers. But I am also an outlier in that I naturally sit below 10% body fat. The only ‘disposable’ weight I have to lose is muscle and that only happens if I stop climbing. Because that isn’t a realistic option for me, there’s no temptation to try. The same isn’t the case for many other climbers, and I have come to realise I am in a slightly privileged position to talk about this—I’m like an outsider with insider’s knowledge.

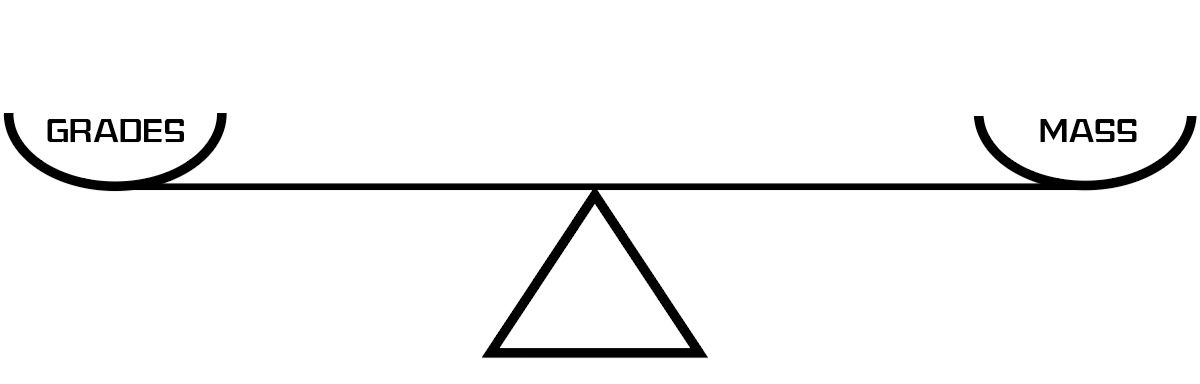

It’s very simple. The idea in climbing is that you can trade numbers of one type for another. Weight for grades, or vice versa. Climbing is a power-to-weight ratio sport—you want to be as light as possible to have a high level of relative strength, and even more so for that strength to be sustainable over multiple moves up a rock. It’s simply a matter of physiology.

Physiology

Not convinced? I invite you to think about the animal kingdom. Smaller animals are generally more agile than bigger animals. Cats are better climbers than dogs. Monkeys are better climbers than bears. Humans are better climbers than horses. In the animal kingdom, scale is a factor in the capabilities of an animal. And there are certain points in physiology where a sweet spot of strength and weight produce the most efficient output for that physiology. We know that ants can carry up to 100 times their own body weight, but humans cannot. But also, ants can’t scale to the size of a human and retain the same capabilities. Fortunately.

We all know that our closest evolutionary relatives, monkeys and apes, are all better climbers than humans. We have flourished as a species not because we are larger (or better climbers) than monkeys and apes, but rather due to other evolutionary traits that made us more effective ground-based hunters. Which makes you wonder why we care about climbing so much, our species clearly opted out of this whole enterprise far back down the evolutionary tree.

To be more specific, the role of scale in elite rock climbing performance makes even more sense when you think about the factors that actually make rock climbing difficult. Hard rock climbing fundamentally comes down to adhering to smaller and smaller rugosities in the rock surface, and moving efficiently between these. The trick is getting small surface areas of skin and rubber to interface successfully with the surface areas of rock available. The holds don’t scale to the climber, generally speaking, so the heavier a climber is, the more force they are required to put through the same surface area of rock. Yes, a bigger climber might be capable of generating more absolute force than a smaller climber. But the required friction interface between climber and rock is not a linear relationship. At certain thresholds of force, skin will tear, rubber will deform and the interface with the rock is lost. The smaller the climber, the less relative force they need to generate to maintain interface with the rock, and to move between holds.

Of course, there is also a point of diminishing returns at smaller scales, where the holds become so far apart that being smaller becomes a disadvantage. Much as larger climbers look to do longer reaches between bigger holds to suit their physiology, smaller climbers will look to do shorter moves between smaller holds, again to suit their physiology versus those in the most-efficient size range.

Within the physiology of humans, muscle size and strength doesn’t produce a linear relationship. Bigger muscles can generate more force, but the more you scale up, the less the subsequent return in strength for the weight involved. (1)

Elite climbers

Within our species, the vast majority of elite-performing rock climbers are of near average height and a ‘wiry’ build. These are small humans, relatively. There are, of course, exceptions to these rules. Every person is unique and climbing has a high level of complexity compared to many activities, which allows for different factors to be both advantageous or disadvantageous, depending on the particular climb and person’s characteristics. But as a general rule, being small and light is an advantage, once you’ve figured out how it all works. (2)

You will occasionally encounter articles or coaching information that make claims that weight is not a statistically significant factor in climbing performance. These don’t hold up to scrutiny—there’s often no representation in their data set for actual high-performing climbers, or the claim is made with asterisked caveats such as ‘within healthy BMI’. We’ll talk about what that means a bit later. If you watch the IFSC World Cups, you don’t see anyone big. You see nearly all people in the 150-175cm height range,(3) with unusually low amounts of body fat and non-bulky muscle types. They look strong and light, or sometimes just light. This body type is so universal that you can be tricked into thinking they aren’t that small, as you only see them in relation to each other. But if you meet these people in person, they are tiny. Especially the women.

This is the picture we get of the most physically capable climbers. You start with a small frame, you add the minimum amount of muscle possible to achieve a certain power-to-weight ratio and then you add as little other extra weight as possible. Fat is seen as ‘dead weight’, serving no benefit to the climber.

Health

In fact, body fat is vital to human health, serving many roles in healthy human functionality. It is well-known that having too much body fat can cause health problems such as type 2 diabetes, strokes, asthma, joint problems and heart disease. It is lesser-known that, outside of straight malnutrition, too little body fat causes its own issues. In women, maintaining a body fat percentage below 20% can lead to a loss of reproductive functionality, as the body goes into survival mode to protect itself from further harm. In men, maintaining a body fat percentage below 10% can lead to reduced testosterone production, a similar survival mechanism. Other health problems related to being underweight include osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease, some cancers and depression.

The Well-Being Of Climbers

None of these problems are outcomes that should result from trying to climb hard. But those wanting to climb hard and looking at the body types of elite climbers can be tempted to reduce their weight as much as possible in order to perform. World Cup and Olympic climbers are role models for high performance climbing and, as climbing increases in popularity and with the high-performance pipeline starting at the youth level, as it does in so many sports, this creates problems.

The first problem is that young climbers can become very serious about climbing as a high-performance sport before they have physically and mentally matured and they and their parents can put a lot of time and energy into this—only to eventually discover that they don’t fit the mould, so to speak. This isn’t unique to climbing, or even sport. Climbing is seen as a free pursuit, a form of outdoor recreation that each individual can perform in their own way. But the truth is that at the elite level, rock climbing is as body-type biased as activities like ballet, gymnastics and basketball.

A more serious problem is that youth are more susceptible to developing eating disorders and that, if their role models are of a particular small body type, the pressure to conform to this body type can become a contributing factor. Eating disorders are already a societal problem influenced by appearance, the added pressure of sporting performance as a further contributing factor is highly problematic.

Furthermore, reductions in bodyweight to dangerously low levels can also be entirely unintended by the individual involved. There is growing research on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S), also known as anorexia athletica. This is where nutrition fails to keep pace with the energy requirements of an individual through the sheer bulk of activity they undertake. This is starving yourself, but by doing too much, rather than eating too little. People suffering from RED-S can eat normal amounts of food, or even more than normal people, but still not be ingesting as many calories as they are burning through activity. This leads to the same bad health outcomes as mentioned above.

This topic has been a high-profile one in the competition climbing scene this year. It is great to see athletes with the highest of profiles, like Janja Garnbret—who is idolised by many young girls, boys and adults for her incredible climbing performances—speak publicly about weight issues in climbing and how the governing bodies need to take a stronger role in ensuring the health of athletes. Indeed, the International Federation of Sport Climbing (IFSC), who run World Cup competitions, have taken a lot of heat over this issue, with consultant physician Dr Volker Schoffl resigning his position this year in protest at their inaction on the issue of athlete well-being.

Dr Schoffl has a long engagement with climbing, as both a long-time climber and physician, he’s naturally interested in climbing injuries and in the health and well-being of climbers. He is involved with the German Climbing Team as medical adviser, and served on the Medical Commission of IFSC since it was founded, in 2009. In his statement after resigning, he wrote:

“We have shown the problem and possible solutions to the sports director and the board of directors over and over again. However, the only confirmation we received was defamation and discouragement. In short, the IFSC may be unwilling to take further action regarding this important athlete health issue and is actively delaying and curbing any decisions that could lead to urgently needed action.”

Dr Schoffl helped to implement an athlete monitoring system for IFSC, where all athletes had Body Mass Index (BMI) recordings done at each event they competed in. If they returned results outside of the healthy BMI range, their national federation was contacted to report the results. However, it was then left entirely in the hands of that national federation, there was no regulatory obligation to act in any way, nor were there stand-downs or disqualifications for athletes who repeatedly measured as underweight by BMI metrics. (4) Even worse, this most basic of monitoring systems hasn’t been active in the 2023 season. (5) Schoffl rightly campaigned for a comprehensive athlete monitoring program be implemented in order to continuously monitor the well-being of competing athletes. This would involve measurements beyond basic BMI, including psychometric testing, which has been established as the only way to tell if an athlete’s mental health has been compromised by the physical demands of training and competing

It is important to note here that all the statements I have made around physiology, scale, normal health ranges and the weights of climbers are statistical generalisations. (6) These are based on comparisons to what is considered normal within a standard deviation. It is true that there are outliers in all of these aspects, as human genetics allows for a considerable range within many parameters. You will see some tall climbers who perform at the highest level, as mentioned above. You will see some big climbers who climb hard. You will see many small climbers who aren’t elite. It is important to keep in mind that we are talking in generalisations, discussing the majority of people who fall within the belly of the bell curve.

Climbing is now a big enough sport that those performing at elite levels are likely on the tail of the bell curve in many of the decisive attributes for climbing. But that doesn’t mean they are immune to these problems.

Take Mina Leslie-Wujastyk. Leslie-Wujastyk is a UK climber who has performed at an elite level in both bouldering and sport climbing. Jen Randall’s 2013 film Project Mina followed her through a training cycle and series of competitions as she attempted to compete in bouldering World Cups. Following that season, and the events depicted in the film, Leslie-Wujastyk suffered health problems symptomatic of chronic fatigue and was eventually diagnosed with RED-S. This illness had long-term consequences for her, both as an athlete and as a person. She required a prolonged break from intense climbing activity in order to normalise her health—simply easing off a bit wasn’t enough for her body to move out of the depleted state it was in. Thankfully, she has made a long-term recovery and is now a mother and has returned to climbing, which has allowed her to talk openly about the health problems she faced.

It is worth mentioning that Leslie-Wujastyk is a qualified physiotherapist and not at all uninformed about health and activity related issues. In the film, she did not appear to be dangerously underweight and certainly didn’t look to be an obvious health risk in comparison to the other athletes she was competing against. For this reason, she did not think she was at risk. Her breakthrough in understanding the way she was feeling came when she compared herself to the other female members of her family, who were all carrying significantly more body fat. She realised at that point that her own physiology isn’t suited to maintaining even a moderately low percentage of body fat. What is acceptably healthy for some athletes, was not for her. Leslie-Wujastyk’s example shows us that you cannot make meaningful assessments based on appearance alone.

As Dr Schoffl has outlined, full metric assessments—including psychometrics—are the only way to be sure that athletes’ well-being is properly taken into account. BMI is a very basic form of assessment (only weight and height need to be measured) and serves only as a starting point for assessing health in athletes. For example, my own BMI is consistently around the 25 mark—this is at the very top end of the healthy range, borderline ‘overweight’. And yet I am a highly active 40 something with unusually low body fat.

While I have talked mostly about World Cup athletes here, climbers becoming underweight while attempting to boost their performance is an outdoor climbing problem too. There are no BMI checks, no federations with athlete monitoring involved in outdoor climbing. Yes, there are sponsors and the climbing media, but they have their own agendas beyond athlete well-being. For an insight into the pressure athletes feel through sponsorship commitments and how this can affect their well-being, I highly recommend listening to New Zealand’s own Mayan Smith-Gobat, who in her Powerband Podcast interview openly acknowledges the well-being issues she faced while supposedly living the dream life of an elite-level, full-time sponsored climber.

Elite level outdoor climbers also serve as role models and are pushing at the very limits of human possibility in hard rock climbing. This isn’t a formalised competition as World Cups are, so the climbing public tends to just pay attention to the reported grades as a way of differentiating between the performance of different climbers. As a member of the climbing media, I admit that I report high grades as they come along, often without much other context. I don’t have the health information of the climbers available to me. I can’t decide what to report based on whether the climber involved had a healthy BMI at the time of ascent. What should I do? I think the answer lies at the fundamental level of how we talk about grades.

GRADES

Many climbers attribute more meaning to grades than is reasonable. Grades are an indicator of approachability, useful in guidebooks as information for prospective climbers to help them select a climb of the right challenge. They are a considerable simplification of the challenges involved in the particular rock climb in question, but this simplification is a necessary evil in this context and for this purpose. In the Ewbank grading system, we use a number scale from 0-40ish. Just a single number, to represent the intricacies of a rock face created by immense geological timescales ridiculing the time period of human existence. Just a number, to represent all the different ways that particular bit of rock might be difficult to ascend for any one human individual—amongst the billions of different human individuals and their varying characteristics. It’s kind of silly, really.

It’s simply not the case that two climbs with the same number grade are of equal difficulty, even for one person, let alone across all people who climb. Climbing is simply too complex to be able to represent difficulty in this way. Completing one climb of grade X is no guarantee that a climber can complete all, or even any other climbs with the same grade. Likewise, it isn’t the case that all climbs with a number beyond X are unachievable for that climber, or that all climbs with a lower number are achievable. It isn’t the grade that the person has climbed when they succeed on a rock climb, it is just that particular rock climb. And that particular rock climb has a difficulty that relates specifically to that individual and their characteristics. This is basic common sense, but it is remarkable how often you hear climbers talk about having climbed a particular grade, rather than a particular rock climb.

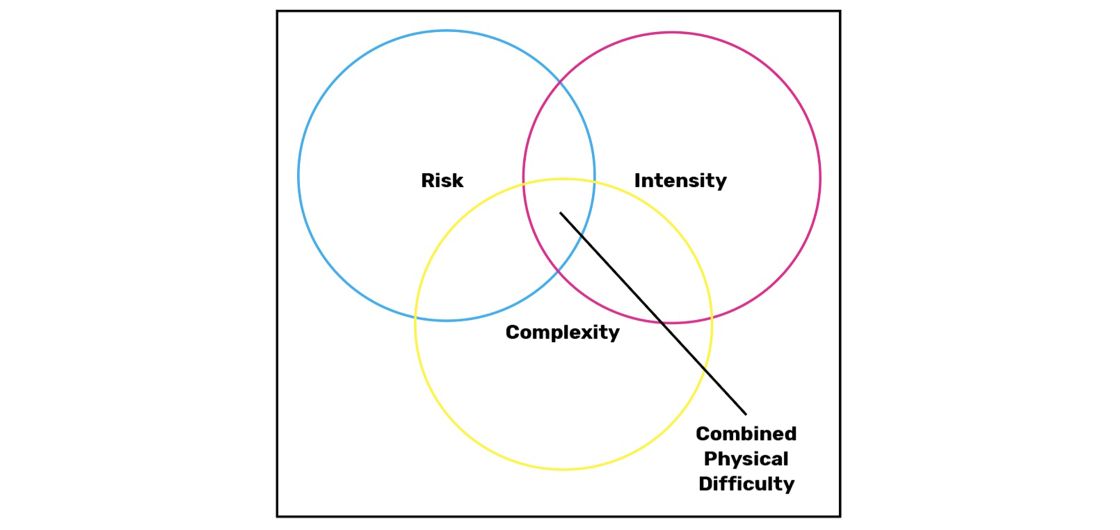

Grades as numbers—and those numbers as indicators of climbing merit—carry some meaning, but that meaning is of very limited utility. One more useful way of thinking about climbing difficulty is the Risk-Intensity-Complexity triad used as a tool by World Cup Bouldering Setters. This identifies three different ways in which an indoor boulder problem can be challenging to a climber. It works reasonably well for routes too.

Risk isn’t necessarily danger. In outdoor climbing, where some danger may be present, risk would cover this aspect. But for indoor setting, it is a type of move that involves a high chance of non-completion by a climber due to involving what we climbers might call a ‘low-percentage’ move. This might be a dynamic stab at a small pocket or slot—a move that feels easy when done correctly, but involves accuracy and coordination that climbers might get wrong as often as they get right. In the context of routes, this can be the same type of low-percentage move, it might not be the crux of the route, but is a place the climber might fall even when they know the route well and aren’t pumped.

Intensity is more simply the application of strength. It is what we typically think of hard climbing as consisting of—fingery moves demanding contact strength, burly shouldery moves, compression sequences and other feats of climbing strength. In route climbing, this can be the same type of moves, or an extended ‘power endurance’ sequence where every move is doable in isolation, but doing them all continuously is very demanding, or even just pure endurance.

Complexity is difficult route reading, unobvious sequences, balancey climbing, coordination moves in the context of World Cup bouldering—generally things related to kinesthetics, rather than pure strength. In route climbing this might involve the ability of a climber to come up with a more efficient sequence than what is most obvious, or an unusual rest position, requiring less endurance for them to succeed on the route than they would otherwise need.

These factors are interrelated and form a sort of complex Venn Diagram, with different amounts of overlap for different climbs. They also vary climber-by-climber. In some cases, a climber can avoid a risky move by bringing higher levels of intensity to a movement—they lock off a move instead of doing a dyno. This might use more energy, but if they assess they have enough energy to complete the challenge this way, they avoid the risk of failing by doing the move the less energy-efficient way. Likewise, you can overcome complexity by taking on risk (just dyno through the hard bit) or by bringing more intensity (just crush that hold and don’t worry about what your feet are doing). You can also, on some climbs, reduce the intensity required by adding complexity through clever solutions like kneebars, sneaky heel-props or other tricks of the trade.

The Risk-Intensity-Complexity triad does a reasonable job of conceptualising what is physically difficult about rock climbing. It is also useful in competition climbing as a tool to find ways to make boulders difficult for athletes to complete without simply asking for higher and higher levels of intensity. Dr Schoffl suggests that if competition climbing overtly prioritises intensity, then it is contributing to athletes being motivated to be underweight, as this is the only factor of the three where being light gives an advantage. So much for the idea that parkour problems in contemporary bouldering competitions only exist because they look good for audiences—this is actually a way of route setters contributing to athlete well-being by reducing intensity. Nevertheless, it is clear that it is hard to express the Risk-Intensity-Complexity factors in the terms of grading with a simple number.

As anyone who has really dived into the world of bouldering will know, bouldering grades are all over the place. I have grown to approach them with a four-grade margin of error, the presented grade can commonly be as much as two grades too high, or two too low, in relation to my own experience of the difficulty. Route grades aren’t much better. Even more confounding, is that you’ll hear plenty of climbers try to establish the grade of a route by some kind of perverse logic, describing the hardest moves of the climb with a bouldering grade (as if that provides some kind of certainty) and thereby calculating that it must be a particular route grade.

Now, as an oversized climber, part of this margin of error is me. If grading is for the average climber, then I am an outlier. But it isn’t that simple. My size can be an advantage on some moves, and a disadvantage on others. This can happen on the same climb. I frequently reach through the crux on a route, making the move shorter climbers find hard look easy, but then fail on the next move—when I have to move my feet while stretched out and holding a small hold. It is very difficult to quantify these varying difficulties using a simple number.

Even if we invent a grading system that accounts for risk, complexity and intensity, these are still massive simplifications of the myriad other ways in which it might be difficult to succeed for any given individual on any given rock climb on any given day. The size and type of holds, the available friction (these would need to be variable to account for the common range of local climactic conditions), the distance between holds, the angle of the wall, the sharpness of the holds, and how polished the climb is are all factors heavily influencing the success of any prospective climber. And that’s without getting into further specifics for any individual climber outside of their strength and skill, such as the reach needed, the hip flexibility required, the size of their fingers in relation to pockets and or slots, whether their shins fit in the kneebar, whether the toe hook is too close or too far away to be of use, etc. While we grade for average climbers, there are very few perfectly average climbers across all the factors involved in succeeding on rock climbing moves. Everyone is unique and brings a different set of strengths and skills and other attributes to the table.

It’s not possible to do the convoluted maths required to normalise grades over every measurable factor that has influence on climbing performance. That’s a fool’s errand. For this reason, grades are a brute force instrument of limited utility. Why then would we use them as an indicator of merit?

Let’s compare two imaginary climbers, in an attempt to uncover some truths about the value of grades and meaningful climbing performance. Climber 1 finds a climb with a much bigger number than they have climbed before, which has a set of characteristics that perfectly suits an aspect of their morphology. Some simple examples of this might be a big span between holds for someone with long arms, or mantling onto a particularly small ledge for someone of small stature with excellent hip mobility. In these examples, the climbers have a large advantage over the average climber, and this might enable them to find success on a specific boulder problem or sport climb with a number several numbers higher than what they’ve climbed previously. It might even be harder than their friends have climbed.

Climber 2 climbs multiple climbs, over multiple years, in multiple different styles and on multiple different rock types. They redpoint grades that their peers are impressed by, because it seems to be at a level on or very near the limit for their physical ability and to do this, they use an intelligent approach that maximises their available strength and skill in relation to the rock climbs they attempt.

Climber 1 might think they have ‘cracked the code’, albeit briefly. At least in their own mind. The number they’ve ‘ticked’ could be 19, or 34, it actually doesn’t matter. If we ignore what the actual number is, then I think it is clear that Climber 2 is a better climber than Climber 1. Climber 2 has made the most of their natural characteristics and maximised their potential. Climber 1 has picked the low-hanging fruit by using an aspect of morphology as a shortcut to ‘success’.

Now, imagine that the morphological trick that Climber 1 uses is temporarily starving themself to become as light as possible. They’ve subjected themselves to a considerable health risk, in order to tick a big number. A number that really isn’t very meaningful. Inversely, Climber 2 can feel proud of what they’ve achieved without even making reference to a number.

This example is of course an abstracted over-simplification. The majority of elite rock climbers are more like Climber 2, but they’ll certainly use all the tools they have available, and this includes using morphological tricks like Climber 1. Someone rock climbing at the limit of their potential ability is inspiring to others, even more so if that limit is beyond that of their peers. But any achievement like this must always be seen in a wide context. Today’s elite climbers are standing on the shoulders of giants, we should attribute their successes not just to them as individuals but to those who have raised them, coached them, supported them, belayed them, and the generations of climbers who have developed skills and tactics to solve complex movement problems and passed this knowledge on to them. It is extremely rare for any single person to be a self-made, independent success on a significant scale.

What we need, when discussing the merits of individual rock climbing performances, is a better, more nuanced take on climbing difficulty—one where we don’t just take the reductive approach of a number and then look for the biggest number.

SOLUTIONS

In the above I’ve attempted to establish that as climbers, becoming too thin in order to attempt to boost our climbing performance potentially jeopardises our well-being. I’ve also attempted to show that focusing purely on grades as a measure of climbing performance lacks nuance and potentially increases this jeopardy. I am far from the first to identify these issues. In an article entitled Applying Statistical Judo To Climbing, Cursed Climbing had this to say:

“We have previously argued that a healthier approach to climbing is one orientated around self-actualisation rather than the attainment of big numbers. However, this is a difficult idea to communicate, especially to those who are most in need of hearing it. Indeed, it is likely that a significant number of climbers have been encultured such that they simply cannot operate in the world without a metric they can maximise. This is a sad fact of life but nonetheless one that ought to be engaged with pragmatically.”

So, what pragmatic steps can we take? Some climbing brands have attempted to shift the emphasis of marketing away from the biggest numbers in climbing, focusing instead on well-meaning stories of inclusivity and accessibility. An example of this is Black Diamond’s sponsorship of Drew Hulsey, a big-boned American climber who works in social services and speaks to the benefits of time spent exercising outdoors. I won’t comment on whether or not Drew climbs well for his size, or otherwise. But you won’t be seeing Hulsey competing at any World Cup events any time soon. This seems like dangerous territory for the brand. What do they do if Hulsey loses a whole lot of body weight and starts climbing harder grades? Would he retain his sponsorship if he was just an average-sized, average-performing climber? Are his sponsors in effect supporting him to maintain an unhealthy bodyweight, just to the opposite extreme?

Brands are in a difficult position, because one thing that grades do is give an immediate impression of high performance, without the need to supply a lot of supplementary information. This is very useful for marketing purposes, where telling long-form stories isn’t always practical as an approach. However, as we’ve identified above, focusing purely on grades creates a false image of achievement. We actually need the long-form stories, the details beyond grade, to accurately tell the individual stories of climbing performance.

There are many positive examples of this in climbing. Lynn Hill’s first free ascent of The Nose on El Capitan, and her subsequent one day ascent is one. Prior to Hill’s ascent, this aid route was the most-striking line on the most striking wall in North America and the first free ascent was highly-coveted. The grade wasn’t relevant in this story—famously, no man had been able to complete the climb, but Hill showed the world what she could do. For the day, it was ground-breaking. Likewise, Alex Honnold’s free soloing exploits have burst through the stratosphere of the climbing world and found widespread popular interest. This is despite the fact that the basic difficulty grade of his most widely-known exploit is no harder than something I redpointed this year. Me, an oversized, non-elite, climbing nobody. The grade isn’t the factor. Another example is Barbara Zangerl, a former World Cup boulderer who has climbed outdoor boulder problems, sport climbs, multi-pitch climbs and trad climbs all at the very highest level, accumulating an impressive resume as one of the best all around climbers on the planet. But arguably her most astonishing achievement is applying this skill and strength, alongside partner Jacopo Larcher, to a phenomenal single-push onsight of Eternal Flame. This much-coveted route involves 24 pitches of free climbing on the south face of Trango Tower (6251m), also referred to as Nameless Tower, in the Trango Group of Pakistan’s Karakoram range. The rock climbing is technical and demanding, it’s at altitude, there’s lots of it, you’re living on the wall in the cold and the climb is partly wet. The grade of the route is again not the main part of the story, but just part of an array of significant challenges.

Telling these long form stories is crucial, as it allows us to look beyond the grade and explore the truly inspirational efforts by some climbers. For this reason, publications like this very journal remain a crucial part of telling our climbing stories. But we can’t always tell the full story, and more straightforward ascents of ‘limit’ boulder problems and sport climbs are still worth noting, even if they don’t have the same level of historical context as the examples above. While we should give grades less emphasis than we often do, they still serve a purpose and we would be better off if we can find ways of using them while also taking into account greater context and nuances of individual ascents.

Alex Lowe famously said ‘the best climber is the one having the most fun.’ This quote is unsatisfactory for ‘serious climbers’. Climbing hard can be fun, but it also requires dedication, sacrifice and pain. It requires a serious attitude that can lead to obsession and unhealthy outcomes. So maybe we need to expand our idea of what climbing hard is. Maybe the best climber is the one climbing the hardest relative to their own genetics and wider context?

If Ewbank grades and BMI are both brute metrics that we are stuck with—one we want to be higher, the other we are tempted to force lower—let’s smash them together. In the future when I am asked the inane question ‘what grade do you climb?’, I will reply with a recent redpoint grade multiplied by my BMI. Afterall, it’s a bigger number. Alternatively, I might draw the person a diagram that shows the interrelated proportions of Risk-Intensity-Complexity that comprised the difficulty of a climb.

CONCLUSION

Numbers—in and of themselves—are fine. But as rationalist philosophers say to empiricists, your data is useless without concepts and contextualisation. Take my word for it, the kind of person at the party who is impressed by someone who is just saying the biggest number, isn’t the kind of person you actually want to make a good impression on.

Trying to just tick the biggest number is juvenile. It is being the person who wants to set off the biggest sky rocket in the box of fireworks. There will always be these people, the ones who just want to tick off the biggest number they possibly can, for the instant gratification. And for some, they’ll risk their personal well-being to do it. Don’t be one of those people, applaud good climbing, not big grades.

The good climbers aren’t the ones who talk about their ranking on the MoonBoard, or who can hold an XXkg dumbbell in one hand while dead-hanging the Lattice™ edge with the other. Don’t be fooled, there are feats of strength and these can be impressive. But climbing is a mix of complexity, intensity and risk—strength is but one factor in a complicated recipe of success.

The good climbers are the ones whose feet stay on the wall when they’re climbing (unless they don’t want them to). The good climbers are the ones who don’t have to drop down a few grades when the style of climbing changes, or the rock is a different type. The good climbers are the ones who onsight trad routes at a grade not far reduced from their sport onsight level. The good climbers are the ones who get a climb done despite poor conditions, sub-optimal logistics or other complicating peripheral factors. The good climbers are the ones who probably don’t even answer when someone asks them what grade they climb.

The more we simplify climbing difficulty to a number, the easier it is for that number to lie to you. To your peril. And if you can’t resist the numbers, recognise that your climbing is individual to yourself and your own context and limitations. Comparing yourself to others is the ‘thief of joy’. And if you really want the biggest number, go on and multiply your grades by your BMI to get even bigger numbers. You’ve only got one life, be kind to yourself.

Notes

1. It’s actually a much more complicated picture than this, where the diameter of muscle fibres plays a more significant role than the cross-section of those fibres, but we don’t need to dive to deeply into this particular topic for our purpose here.

2. Some hyper-elite climbers are taller than average, but they tend to be very thin and more in genetically abnormal territory, with hyper-mobility in their joints or other physical outliers that allow them to use the benefits of greater reach without the normal negatives that accompany this.

3. Again, there are a few outliers, but the taller athletes than this are also even more unusually lightly-built.

4. It should be noted that different federations have completely different attitudes in this respect. The Austrian Climbing Federation, to their credit, have independently adopted most of Dr Schoffl’s recommendations and as a result their top-level athletes are continuously monitored for well-being by a range of metric testing. Based on the results from the World Championships this year, this seems to produce positive outcomes for athletes.

5. IFSC have ducked this issue, signing up to the Olympic Commission’s own protocols from the 2024 season on. Time will tell whether this set of protocols is specific enough for the sport of climbing.

6. There’s of course a lot of science involved in all of this discussion—data sets which I have purposely avoided getting too deep into, as this article is long and dense enough as it is. Needless to say, I am confident enough in the summaries I have made around healthy bodyweights and muscle physiology to make these conclusions. However, as a climber and as a human, I encourage you to do your own research and learn as much as you can about how your body works and take responsibility for your own health.