Expedition Report: Leaving Las Vegas

When it comes to going on a climbing trip (or in this case an expedition moderne) my initial intentions are for conquest or experiences relating to the rock, through successes on the grander scale (actually ascending specific lines), or through discovering styles of climbing not all that familiar to me and learning how to use my body to interact with that style. The latter being a very worthwhile goal when it comes to bouldering, as success through topping out can be few and far between at times. However I always seem to remember once actually in the destination I choose to be climbing in, that all the other experiences that make up one's time on adventures like this are generally the experiences that I remember, or are the experiences which I would not be able to experience anywhere else.

For two weeks now we’ve been living on the ground floor of this building, divided into four apartments, copied and pasted for as far as I can see down either side of the road. There's a fake yucca plant in the corner and a picture of a seashell in a golden frame hangs on the wall behind me. Jonty is sleeping on a worn-in, brown tweed couch which we keep finding ticks in. The house across the road has two cars with flat tires parked outside it and, until it got towed a couple of days ago, we also had an abandoned car with a flat parked in front of our house, perhaps the last guest to stay here.

Once a week, an ice cream truck does the rounds of the neighbourhood, playing through terrible quality speakers a song which is familiar to my ear but only in the context of trucks with cold dairy products in them. Twice now we’ve run out as it drives by our apartment, waiting at the door till the last minute so we’re not standing on the curb for too long attracting attention to ourselves. Rummaging in our pockets to make up the change for an ice cream cookie sandwich going for $1.35. Returning quickly back to the safety of our tick den once the transaction has been made.

It is quite an incredibly violating feeling discovering a tick on your body, at least to a New Zealander unfamiliar with such creatures. I found the first in the mirror, latched to my collar bone. He was the size of a child's index fingernail, and could not be flicked off. Due to his location I couldn’t actually see him by looking down at my chest. He’d discovered my blind spot… deliberately? It’s impossible to say. Pinching him between my index and thumb I ripped him out of me and held him up to my face to get a good look at him. All six of his reddish legs were wriggling around in a desperate attempt to escape but they could find no purchase. His two black beady eyes nestled underneath the shield plate that was his back, and in his two pincers he had in front of his mouth he held a small chunk of my flesh. That little bastard.

For the next short while he lived under an upturned glass, our makeshift observation tank, until we had determined whether or not I would be contracting some sort of exotic disease. So far, no symptoms have revealed themselves, although three other ticks have. Scratch that, five ticks now, they’re all around us. Alec is nervous about a red lump on his back and we haven't climbed any boulders.

We continue our attempt to ascend rock climbs while our tick fiasco continues on in the background. On Erica’s final day we went to the Gateway area, a sandstone canyon of incredibly visually appealing rock, with a bunch of low grade rambleable climbs, where we could get as much climbing in as we could.

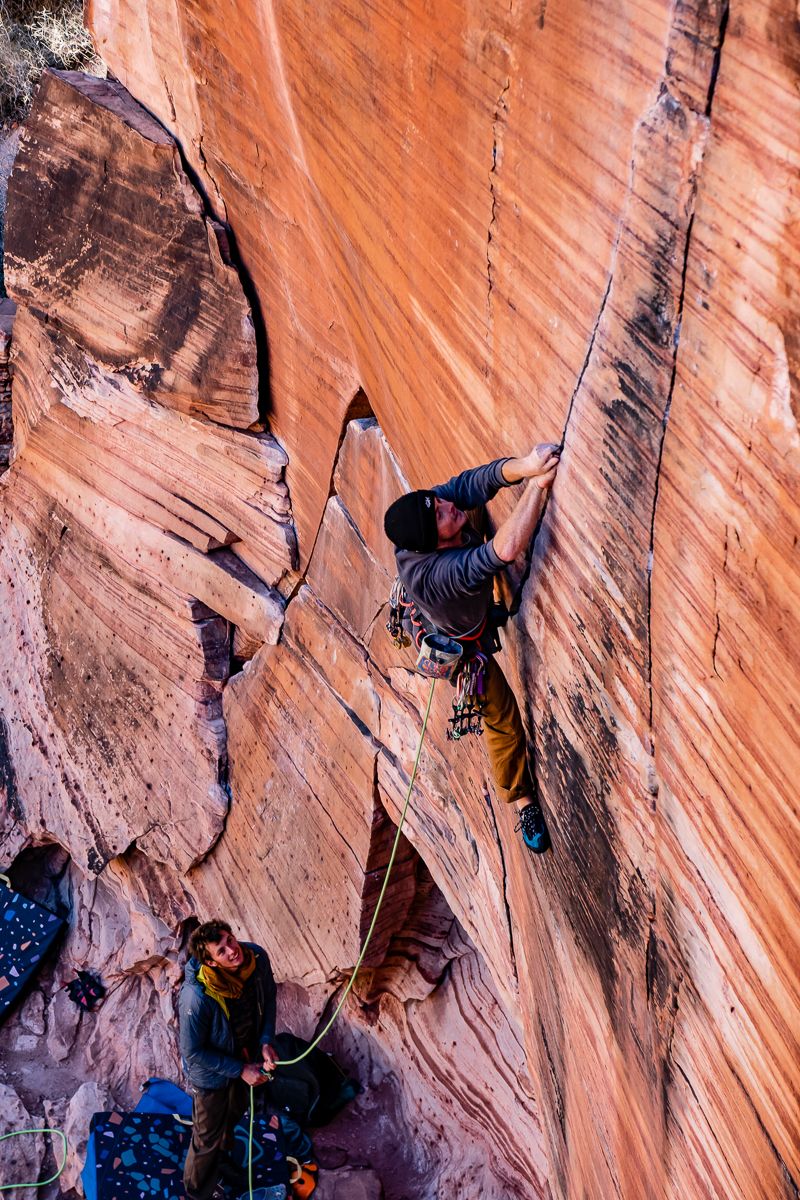

Through geological occurrences I am unable to understand, the rock, a soft sandstone that with too aggressive brushing could easily be damaged, displays beautiful swirls and stripes, blotches and dots. The rock in Gateway is straight out of a 1950 abstract expressionist gallery, showing works from all the avant garde greats. Pollocks’ drips are strewn across the rock. Rothko’s muted and introspective hues are found in the depth of the colours. Kusama’s polka dots are comically seen in the three-dimensional nipples sporadically dispersed around the place. Twombly’s red swirls are in every direction you look. Walking through that canyon is an incredibly visually stimulating experience, it becomes overwhelming and then it just fades into the background and you start to forget that every piece of rock is a work of art. Where once raging flash floods careened down the gully, now dry water-worn slabs with channels and grooves, runnels and sheer slabs lie. An incredible challenge to interact with. Moving in, out and around these sculptures is a very satisfying experience.

And so on this last day for one member of the sub-alpine team, we walked through this canyon and danced, played and climbed on these features, up where once water ran down. Another appealing attraction to the Gateway area were two searing crack lines of slick sandstone. Having a background in ascending such features, Erica and Jonty swam their way up the both of them, showing to us boulderers the finesse of technique in a style you won't find at the Hill. Their ascents were a joy to witness, as compared to my feeble attempt that got no further than a metre and resulted in myself leaving with less skin than I arrived with.

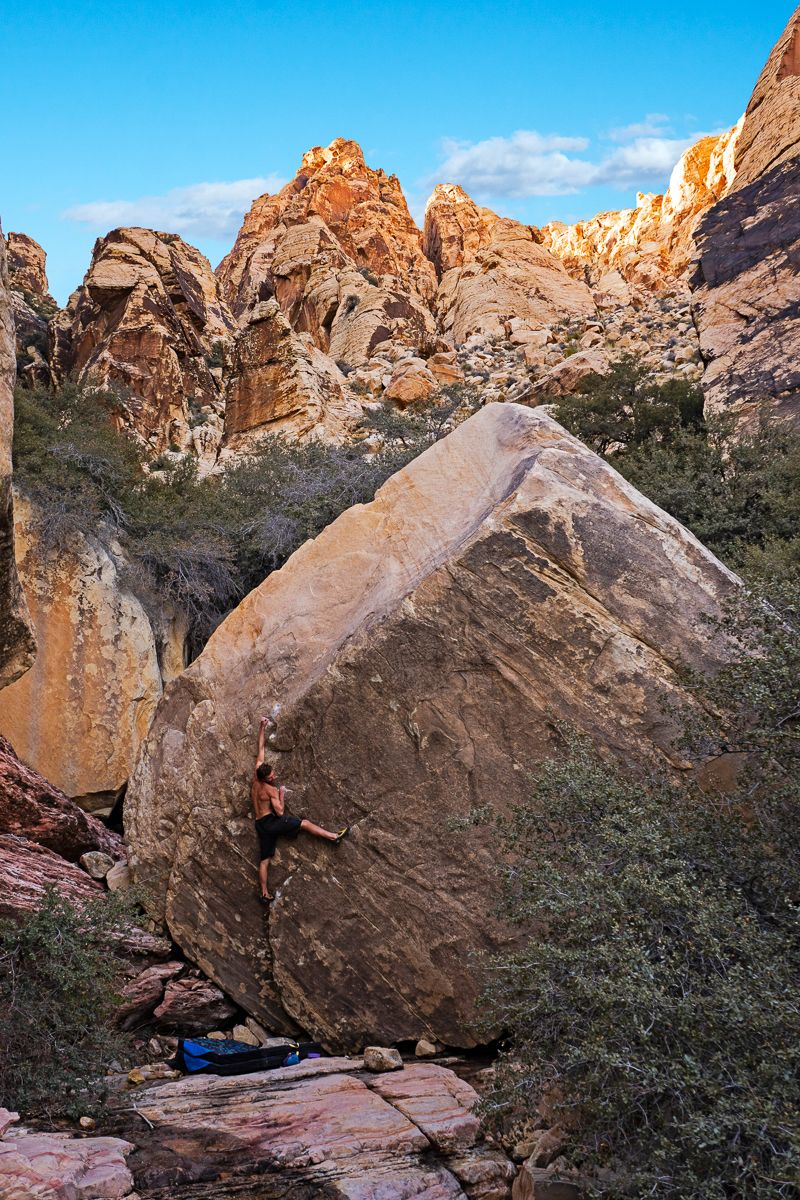

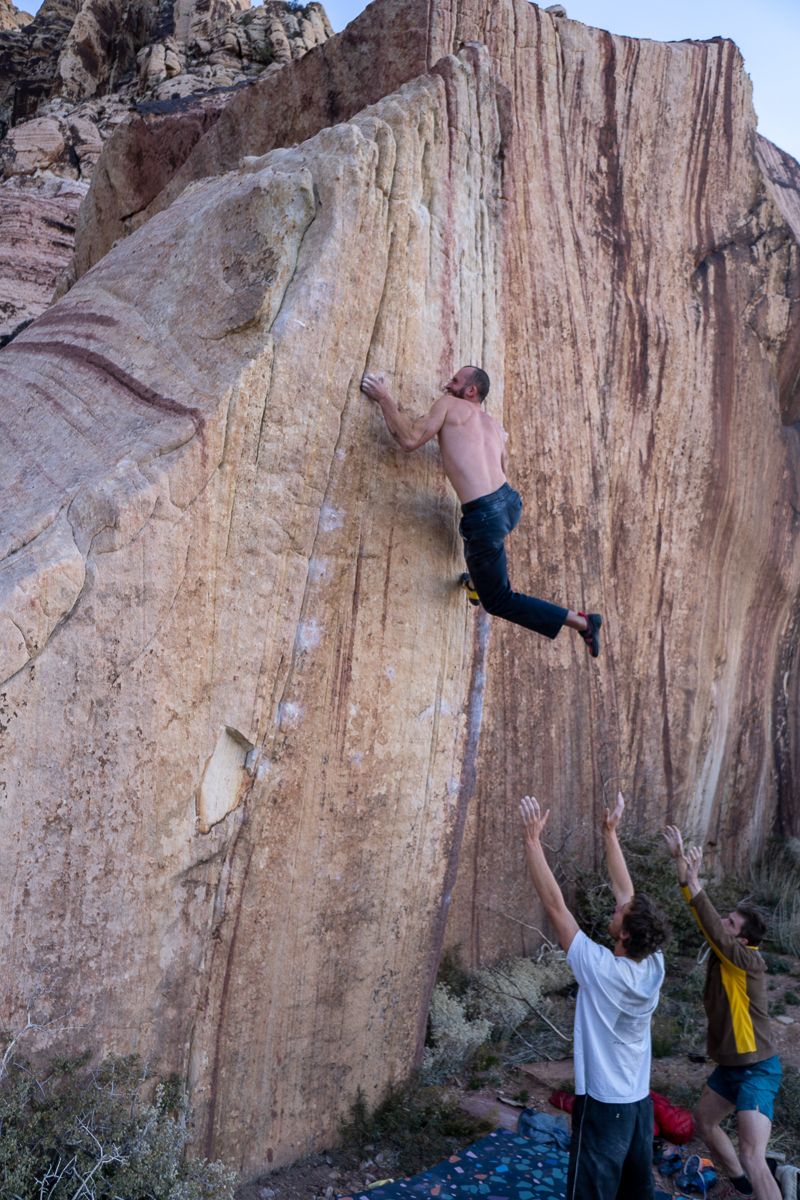

Isaac discovered how to try hard again. Years of climbing on the low angle undulations of Castle Hill has meant that he hasn’t had to go “full ballistic” like he used to do. The tail end of our trip to Red Rocks was the setting for a couple of incredible power screams, head snatches and dropping of “the clutch”. It’s always impressive to see someone give it everything they’ve got and scrape up a boulder by the skin of their teeth. With his rediscovery of the lost art I’m hopeful to see what he can do on future steep blocks with edges and yarding.

Walking back from our last days bouldering in Red Rocks, the sun had long set, only a vague discoloration of the night sky along the skyline of mountains and canyons was all that suggested its existence. The moon had not yet risen but our path was illuminated by the light pollution of Vegas. A vague dusty path meandered out of the canyon and swerved in and out of the cacti and shrubs. The Joshua trees, which in the light of day can convey all sorts of emotions through the positions of their branches, mimicking the human form with their limbs stretching out towards the sun or drooping down to the earth, now with the lack of light appeared less expressive and much denser than they usually would.

This hour-long shuffle through the sand was a great opportunity to reflect on our time here. Red Rocks was an unexpected challenge in the approach to climbing. With the nature of these canyons, each day we would select one area to go to that would have no more than a handful of boulders in them, on occasion we would be walking for an hour or so up one canyon for just one boulder. Hedging your bets for the whole day's climbing on whether or not that one boulder was worth climbing. Sometimes they were not. This unavoidable feature of the bouldering here meant that the days disappeared into indistinguishable treks up into the canyons.

This all being said, the walking here is world class. The canyons are a beauty I haven’t experienced before. Once you escape the endless expanse of flat desert and get into the steeper terrain, the landscape completely changes, as does the flora which is surprisingly luscious. Juniper trees, Pines, Barrel Cacti and my personal favourite the Manzanitas, which are a large shrub with small circular leaves and an incredibly smooth, red ochre pigmented bark, which contrasts wonderfully with the grey, deceased branches that still cling to its trunk.

I’m glad we came to Red Rocks, not because the climbing was out of this world, or because we sent loads of boulders (because neither of those things happened), more so because our trip here has shown me that we have climbing in New Zealand that is far more compelling than many of the well known overseas destinations.

Our next stop on this adventure of perspective is Bishop, a destination with a promising combination of large-scale rambles and higher density boulders.

-By Matt Corbishley, with photos by Isaac Buckley.