Rock Shoes 101

Newish to climbing? Have you been hiring shoes in the gym up until now, or worn out your first pair of shoes and wondering what to buy next? Or are you simply sick of seeing others stand comfortably on footholds that you struggle to make good use of? Fear not, here is a guide I’ve put together based on two decades of experience buying climbing shoes.

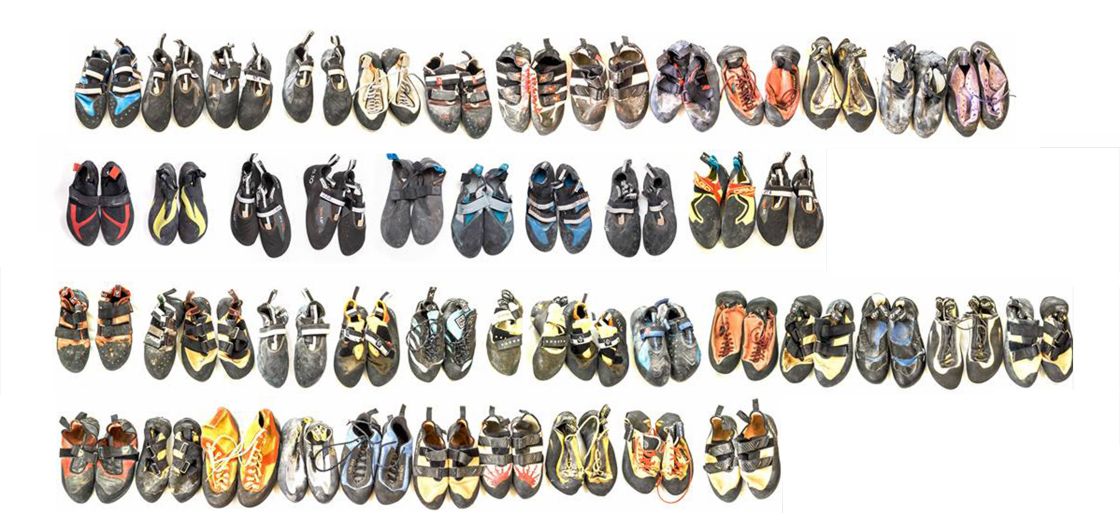

Below I’ll attempt to explain all the basics and shed some light on some of the lesser-known considerations of choosing a good pair of shoes. What should become clear is that there is no ‘best climbing shoe’ across the board. Different designs work better for different things, and fit is extremely important, so some shoes just won’t work for some people, given the variety of foot shapes and volumes out there. For this reason, I’m not going to recommend any specific models. However, I’m also including a number of short reviews of favourite models by a range of successful and experienced climbers. In these reviews, the author will describe what aspects of the shoe work for them, so even if that particular model doesn’t fit you or is no longer available, the information should still help you think about what performance characteristics are important in your climbing and help inform your own selection.

Fit:

This is the single most important factor in getting good performance out of your shoes. You can have the most aggressive last out there, plastered with the stickiest rubber available, but if the shoe is too big or too small, you aren’t going to be able to make proper use of it. Sizing of climbing shoes is problematic, because it isn’t consistent across brands, or even within brands across the different models (in some brands I wear my street shoe size, in others I wear 2–3 sizes smaller). It is highly-recommended you try a pair on before handing over any money. Even if you’ve owned a particular model of shoe in a certain size before, there’s no guarantee that just buying the same size sight-unseen is going to work out. These shoes are handmade and there are natural variations in how they fit. Some brands have horrible reputations for not maintaining size consistency within their models across periods of manufacture. The only way you can guarantee the right fit is to have tried on the exact shoes you are going home with. If you want to be able to do this and have stores stocking shoes to try, you should always buy locally if you can.

Having said all this, I’m a size US14 and can rarely get the shoes I want in my size locally, so I’ve been through the hoops buying shoes online many a time. Based on this experience, this is my advice. If the shoe you’ve identified as your first choice isn’t available locally, ask local retailers if they can get them (they aren’t going to stock things if they don’t know people want them). If you have to order online—and this should be a last resort— make sure you’ll have the ability to exchange for a different size (you’ll often have to pay for shipping again at least one way). You should calculate this into the cost before deciding online is ‘cheaper’. Every time I make the mistake of going on to Facebook I see many people selling near new shoes they’ve bought in the wrong size and are trying to sell on to others. Along with scores of people selling completely worn out shoes with holes in them, and pretending they still have some life left in them—please stop. One way to bypass this inevitable wasting of time and money is to find someone else who has a pair of shoes in your size to try on. Even if they don’t fit, you now have a data point. Sometimes you can cross-reference with other shoes you know your size in (and some online retailers such as bananafingers offer this ‘size calculator’ service across many models, but this isn’t a perfect system and should only be relied on as a last resort).

Having said all this, I’m a size US14 and can rarely get the shoes I want in my size locally, so I’ve been through the hoops buying shoes online many a time. Based on this experience, this is my advice. If the shoe you’ve identified as your first choice isn’t available locally, ask local retailers if they can get them (they aren’t going to stock things if they don’t know people want them). If you have to order online—and this should be a last resort— make sure you’ll have the ability to exchange for a different size (you’ll often have to pay for shipping again at least one way). You should calculate this into the cost before deciding online is ‘cheaper’. Every time I make the mistake of going on to Facebook I see many people selling near new shoes they’ve bought in the wrong size and are trying to sell on to others. Along with scores of people selling completely worn out shoes with holes in them, and pretending they still have some life left in them—please stop. One way to bypass this inevitable wasting of time and money is to find someone else who has a pair of shoes in your size to try on. Even if they don’t fit, you now have a data point. Sometimes you can cross-reference with other shoes you know your size in (and some online retailers such as bananafingers offer this ‘size calculator’ service across many models, but this isn’t a perfect system and should only be relied on as a last resort).

If you have the cash and are tight on time, the only way to really guarantee getting a pair that will fit without the ability to try them on is to use a technique I call ‘size bracketing’. Simply order the same shoe in what you think is the right size for you, plus the size up and the size down. Keep the pair that fits best. I am fortunate in some respects in that I’ve never bought a pair that were too big, as I am at the upper limit of what is made and even outside the range in a lot of ‘high performance’ models. When climbing in Ceuse, I stopped by the climbing gear store in Gap to look for a new pair and when I told the guy in the store my size he laughed and said, ‘we ‘ave no good shoe in zis size, nobody with feet like zis can climb ‘ard’. He was right, of course. I simply buy the biggest pair they make and it either fits or is too small.

Last:

The shape and overall volume of the shoe is dictated by the shoe’s last. A last is essentially a model of a foot that the shoe is designed around. It dictates where it is wide and where it is narrow. Some manufacturers will have a last they use across a range of models and tell you which shoes are made in which last. A prime example is Five Ten’s Anasazi last. While there have been a range of different coloured shoes with different fastening systems and varyingly comical heel shapes carrying the Anasazi name over the years, these all—in theory—fit in a similar way (Five Ten’s notorious size variance issues aside).

The aspect of fit that is most important to get right is the length of the shoe. Generally speaking, shoes will stretch a bit for width, but not for length. The length of a shoe is primarily dictated by the numbered size, while the width does change as the size changes (the last scales up and down with the size), the general width and shape characteristics of the shoe depend on the last. Some lasts will work for your feet, some won’t. It used to be the case that each company would only really use one last, or a few very similar lasts and so the whole range of a brand would be known to fit ‘narrow’ or ‘wide’. Currently, there are more companies and models available than ever before, so there is plenty of selection and no reason not to be able to find a shoe that fits well. Most brands offer a range that will include wider models and narrower models and different shaped toe boxes.

In fact, it has become increasingly common for brands to produce a women’s version and a men’s version in the same model. These are usually a smaller and larger volume version of the same last, respectively. Unhelpfully, sometimes the last is the same and just the colours are changed. It would be better if companies simply used low and high volume labelling, instead of gender, but marketers have had their way. Nevertheless, don’t be afraid to try on something supposedly aimed at a gender you don’t identify with if you are having volume issues. I know of a few male climbers with low volume feet that favour something like the women’s Solution from La Sportiva over the men’s version, and vice versa.

In my experience, the key aspects of a last to pay attention to are the width of the shoe across the forefoot (where your larger toe joints will sit) and how pointy it is in the front. The mid-foot volume of the shoe can be adjusted by laces or velcro unless it is way wrong (or a slipper with no fastening), but generally the toe box can’t be adjusted, and this is the primary performance area of the shoe anyway. The mid-foot fit and heel area are still crucial for things like heel hooking, but unless you are a heel-prop king like Bob Keegan, this is usually of secondary priority to the toe area. The bit of the sole about the size of the last part of your thumb at the very front of the shoe does 99 per cent of the contact with the rock on crucial footholds. If another part of your shoe is in contact with the rock/plastic then you’re basically standing on a ledge and performance is irrelevant (heel and toe hooking excluded).

Lasts vary from quite pointed and asymmetrical in the toe box, to a more symmetrical and quite rounded shape in the front. Generally, people will find one style works better for them than the other, based on the length of their toes and the length relation of their big toe versus their other toes. Try on as many shoes as you can in a shop and from other people with the same size feet and pay attention to the shape of the ones that feel best. Look for shoes with a similar shape when choosing your own. Ideally, you want your big toe to feel supported and like it is in alignment and position to do most of the work unimpeded. Personally, I find the more symmetrical and rounded shapes put my big toe in a weaker position in relation to the very tip of the shoe and I favour quite strongly asymmetrical and more pointed shapes to the toe box.

So, how should a shoe made on the correct last for your foot and in the right size feel? Climbing shoes aren’t designed to fit like street shoes, your foot should be snugly supported without any excess room or baggy spots. But, if your toes are too bunched and fully-compressed, you won’t be able to use them properly and they will be very painful (this can also lead to issues like bunyons and joint problems such as hammer toe). Likewise, if your toes are sitting fully flat in the shoe, then they are going to be comfortable, but your toes are in a weaker position and will be able to move too much inside the toe box of the shoe for stability on smaller footholds. I would describe the feel of putting on a climbing shoe with a good performance fit to be like wearing a sock a size too small without any stretch, or a ‘glove-like’ fit, but for your feet. Come to think of it, climbing shoes should probably be called climbing foot-gloves, rather than shoes. Then people might stop wearing socks in them. But then I suppose they are a foot-mitt, rather than a glove, technically speaking …

The important thing is that your toes are held in a ‘crimped’, slightly-bent position—as this is their strongest position. You should still be able to bend them very slightly away from the front of the shoe, but this should be relatively hard to achieve. New shoes will all wear in slightly to give a bit more room in this area, so if you can move them too much on first try, then they will likely become too sloppy quite quickly. For me, the key is to have the room to be able to wiggle my toes in a retracted, bent position, but without them actually pulling away from being in contact with the front end of the shoe. I admit that this is slightly subjective and just how tight a shoe should be does vary between climbers with excellent footwork. It’s likely that the differing length of people’s toe bones and the flexibility of toe joints dictates some variance in what works best for different people. A good rule to go by is that if they are really tight and too painful to wear for a whole route when new, they are likely too small. You need to be able to actually stand on the footholds without hurting your toes, or you aren’t going to enjoy climbing. But, if your shoes are so comfortable you don’t take them off between routes and can wear them for a whole session of bouldering without needing to relieve a bit of toe pressure, I’d argue you don’t have a performance fit.

A disclaimer: not everybody is looking for a performance fit, some people value comfort over performance. Others want a pair of shoes they can wear for most of a day on a multi-pitch alpine rock route and are prepared to sacrifice a bit of the top end of a shoe’s performance to achieve this. That is totally fine and easier to come by than a good performance fit.

The point of this guide is that comfort and performance are not mutually exclusive. A good fitting pair in the right size should be able to give you excellent performance without significant discomfort. Don’t forget to pay attention to what time of day you try shoes on, in the morning and in colder temperatures your feet will be smaller, they tend to swell slightly over the course of a day and when it is warm.

Rubber:

Outside of a good fit, rubber is the key performance difference between shoes. Just how much of a difference it makes is something that climbers have been arguing about around campfires for many a year. Some people insist that they can’t tell a difference between rubber types, others will flat out refuse to even consider some shoes because of the rubber on them.

Personally, I can tell the difference between some different rubbers. My pair of Five Ten Team VXI with Stealth Mi6 rubber stick better than anything else I own. Part of this is that the shoe itself is very soft and sensitive, as well as the thin rubber on the sole and its friction characteristics. Five Ten’s hype around this shoe and rubber was that it was designed for better friction on smooth surfaces and made for Tom Cruise to wear while doing his own stunts in the movie Mission Impossible 6 (Mi6), specifically standing on the exterior glass of Burj Khalifa. I don’t care about this in the slightest and I haven’t seen the movie. But the rubber is sticky, for sure. On the polished footholds at the Cave, at least. However, I’d not try and wear these shoes on a face climb with small edges, if I had another option. The soft rubber would deform too much and roll off, as well as the shoes not providing enough support.

The thing is that rubber, like any other attribute of a shoe, has become specific enough that no one option is going to be the best in all possible cases. Generally speaking, softer rubbers are better on more uniform, finer-grained surfaces as a soft rubber is better able to conform to small scale rugosities. But put too much strain on a softer rubber through a small surface area and it will deform (there is a separate rubber property to hardness, known as resilience, which plays a role in this, as well as other properties such as rebound, but lets not go too far down the rubber rabbit hole). So in some cases, a slightly harder rubber gives better performance.

The differences in hardness of rubbers is measured on the durometer scale. A running shoe sole is around Shore 70A on the durometer scale, while a rubber band is Shore 20A and a pencil eraser Shore 40A. The wheel on a supermarket trolley is around Shore 100A.

So where do climbing shoes sit on the scale? Well, most companies won’t give you any real technical information, they just claim their rubber is the stickiest across the board. That probably isn’t true for any of them. Relative industry newcomers Unparalled provide significantly better information than most, listing several technical properties for each of their rubbers, including durometer. Their softest rubber measures a Shore 45-50A, but they use up to a 75-80A on some models. I’d estimate that most climbing shoe rubbers are in the 60-70 range.

To get a bit more climbing specific, if you are smearing at the famously glassy and low-friction, fine-grained limestone of Castle Hill Basin, you are going to do better with a softer rubber. For a long time, many of the most successful Basin boulderers claimed to notice a difference using the Stealth C4 common on Five Ten shoes, versus the harder rubber from Vibram on La Sportiva shoes. But on harder rock types, where tiny dime edges and granite crystals are going to be able to take a lot of your bodyweight without crumbling, a harder rubber is going to stick better and this has been evidenced by La Sportiva shoes with the harder Vibram rubber excelling in places like Yosemite’s El Capitan. As I’ve said already, there is now a much greater range available and this ‘one choice or the other’ rubber selection we lived and climbed with for years is no longer such a binary dichotomy. For instance, Vibram now make a range of compounds (XSGrip, XSEdge), Stealth from Five Ten/Adidas have C4, Onyx, HF and Mi6 as well as the varying options from other manufacturers like Unparalled.

Think about where you do most of your climbing and what kind of footholds are the norm there and choose appropriately. My advice is to prioritise the footholds that give you the most trouble, so if you climb somewhere with a lot of edges, but the edges are predominantly fairly large and easy to stand on while the odd smear is causing you grief, then going with a softer rubber might help. But remember, the softer the rubber the faster it will likerly wear out, so if your footwork is a bit sloppy then you’ll get much better mileage out of a harder rubber.

Flat or downturned:

The remaining key performance characteristic of a climbing shoe is its profile. Ever since La Sportiva’s famous Mirage shoe, with its radical banana shape, manufacturers have been producing varieties of downturned shoes aimed at steep climbing—alongside the more traditional flatter profiled models. A downturned shoe gives a slight hook to the toe area and this allows you to toe-in and pull outwards on positive holds in roofs and steep terrain. In steep climbing, the more you can keep your feet on the rock the more efficient you are, so this technique is extremely important. You can still do this in a flat shoe, but they are generally less-effective at it and more prone to suddenly releasing and demanding more energy from your core to hold a footless swing.

The trade-off is that for this technique to work is that the shoe (and the rubber) really needs to be soft and sensitive so you can feel when the pressure is holding. As you are likely putting less of your bodyweight through the shoe, this is okay and becomes a specific design characteristic. But these shoes are going to be less-effective on low-angled climbing where you are putting a lot more weight through your feet and often on small edges. A softer rubber and softer shoe can do this, but it is harder on your feet and the rubber can deform too much in some cases. A really downturned shoe is also not usually going to be as good at smearing, as this essentially requires it to deform from its downturned shape, past a flat profile and into a smearing position. If the shoe is really soft and not sized too small, this will still be possible, but you’d arguably be better off in a flat profiled shoe with the same level of flexibility.

Extremely downturned shoes are often touted as the ‘highest performance’ and sexiest models. But these are like a high performance sports car, where if you do most of your driving on suburban streets then you can’t actually use the performance and have wasted a bunch of money on a less comfortable option. If you do lots of steep climbing then a soft, downturned pair of shoes is essential. But if you are only going to own one pair of shoes, then you’re likely better served by something less aggressive most of the time. If you climb predominantly on faces and slabs you’ll suffer unnecessarily in a downturned shoe.

Upper Materials:

It used to be the case that most shoe uppers were made of unlined leather. Vegans were all out of luck. The other problem was that these shoes, especially slippers with no way of adding tension, would stretch and stretch and stretch for width. Shoes like La Sportiva’s Cobra and Five Ten Mocasyms would fit great out of the box, but eventually their toe box would expand to the point where they were useless for any kind of edging performance (not this style of shoe’s strength to begin with anyway) and the heels would peel off with the mere hint of a heel hook. But, you could still wear them as ‘sloppys’ for warming up in, and for training when you don’t want to wear out your good shoes. A pair of sloppys are a valuable—but not essential—part of any shoe ‘quiver’ (I’ll go into shoe quivers in a follow-up article: ‘Rock Shoes 201’). Admittedly, this was a problem experienced more by heavier climbers with bigger feet. The more force you are putting through a shoe, the more it is going to want to stretch. Add in to this that there is a greater amount of material to stretch in a bigger shoe, and the problem is exacerbated. If you are a small person with feet below the average size, an unlined leather shoe is probably still a reasonable option. For everyone else, a lined leather or synthetic shoe is going to be better in the long run.

These days, a lot of shoes are lined. See if the inside of the shoe looks like leather or instead has a fine canvas or other material look to the inner. Confusingly, many shoes are now made entirely out of synthetic textiles, but some of these are made to look like leather. The shoe should come with a textile label or sticker which symbolises what part of the shoe is made from a synthetic textile versus leather to help clarify.

A lined leather shoe is going to be slightly thicker in the upper and as a result less-sensitive than an unlined shoe. If you are buying a stiffer edging shoe design, this is probably ok. But you might enjoy a synthetic material as these can provide a bit more sensitivity while still avoiding the stretch problem. They can also have other characteristics you may or may not need like moisture wicking and odour repellency.

If looking for a shoe specifically for steep climbing, you may want to prioritise sensitivity over anything else. Pay in mind that durability can also be an issue. My pair of Team VXIs have a synthetic microfibre upper which is very soft and sensitive and also very light. They are the only pair of rock shoes I’ve owned out of around 30 pairs in total where the upper has worn out before the sole, with the material around the pull on heel loops completely disintegrating. Bear in mind that this is on a shoe with only 3mm of very soft rubber on the sole from new, so you’d really expect the rubber to wear out first.

Stiffness:

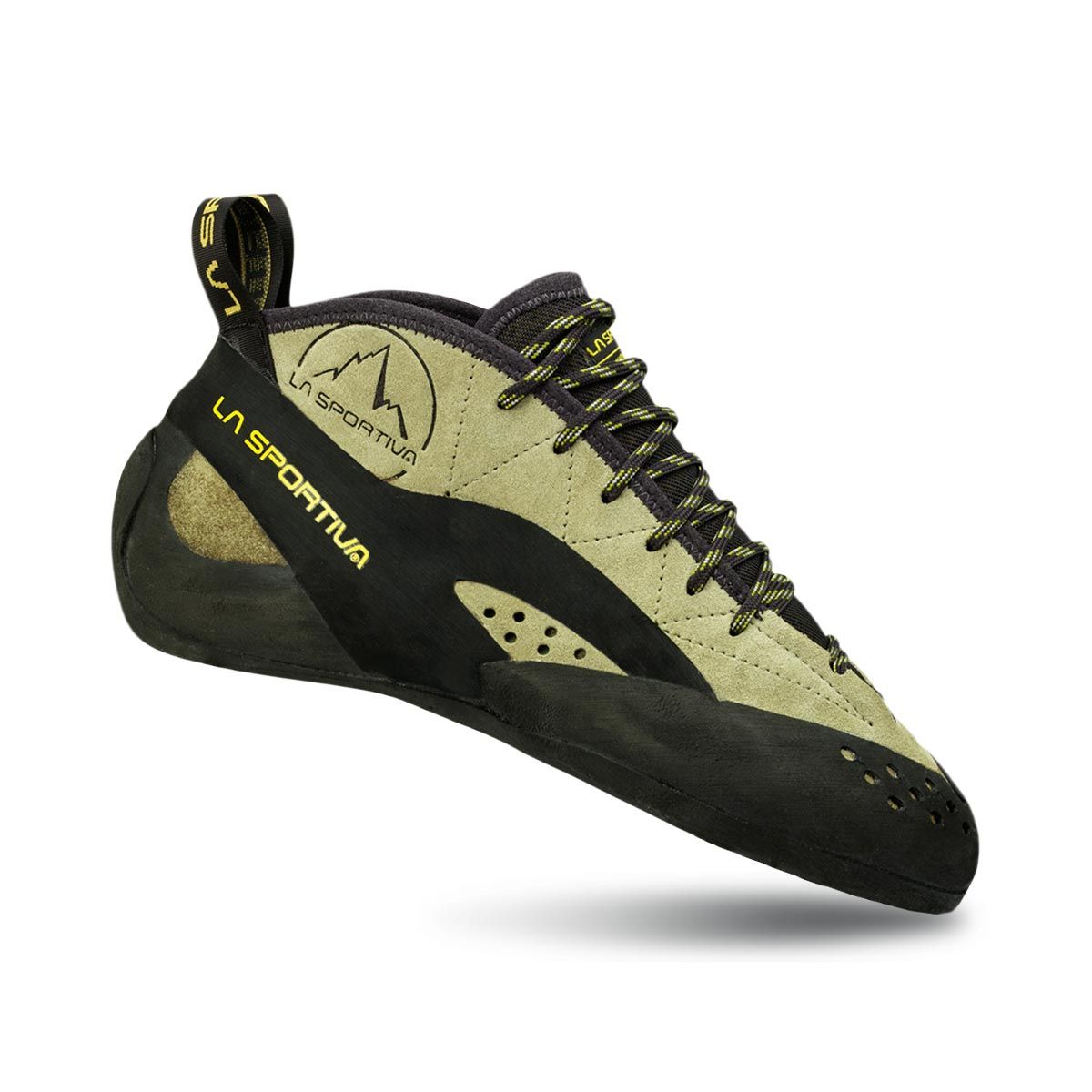

As mentioned above, the stiffness of a shoe can vary quite substantially. The feel of a shoe is made up of the properties of the upper materials, the thickness of the rubber on the sole (this can vary from 2.5-7mm) and the performance of the mid-sole. The midsole sits below the foot between the upper and the rubber sole and its job is to provide the supportive structure to hold the shape of the sole when standing on footholds. In extremely soft shoes, like Scarpa’s Furia, Five Ten’s Team or La Sportiva’s Theory, this midsole is very pliable and minimalist in order to prioritise sensitivity and suppleness. In a very stiff shoe, like La Sportiva’s TC Pro or the fibreglass in Five Ten’s old Anasazi Mesa, the midsole provides a lot of support for standing on small edges and crystals without the foot becoming quickly fatigued, but this comes with a lack of ‘feel’ or sensitivity through the shoe.

It used to be the case that the midsole of a shoe would degrade over its lifespan and people would buy stiff shoes and use them for edging early in their life, then as they became more and more worn they would be soft enough for smearing and more sensitive footwork and overlap with another newer pair carried for edging. More recently, companies like La Sportiva have promoted the characteristics of the P3 midsole to retain a similar performance of the midsole characteristics through the life of the shoe. Other technologies are things like the Solution ‘fiddy cent’, where the shoe is generally pretty soft and sensitive but with a small but firm implant in the midsole just under the end of the big toe, for more support just in that key area. Five Ten also tried the ‘oreo’ mid sole in their short-lived Southwest shoe, this had different properties by orientation, claiming longitudinal flexibility for smearing but lateral stiffness for edging. This sounded great in theory, but was quite thick and insensitive and never appeared in another model.

One thing that I haven’t been able to discover is how many manufacturers vary the stiffness of the midsole by size. Five Ten’s old Hueco model used to come in a variety of stiffnesses corresponding to the size going up. This makes sense as a bigger foot is generally going to be attached to a bigger, heavier human standing on a relatively smaller foothold. Chances are that bigger shoe is going to need to provide more support as all the forces are higher. I’ve never encountered another manufacturer talk about this in their marketing material, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t doing it.

As mentioned above in relation to materials and stretch, logic suggests that a soft-styled shoe is going to be relatively softer for a heavier person with a bigger foot, so if you are a small-footed light person with relatively strong feet then even moderately soft shoes are going to feel quite supportive, while a TC Pro is going to feel like ‘crampons for granite’ (‘crampons for granite’ can be a good thing, if you are spending all day on El Capitan stuffing your feet into cracks, then a bit of support and protection is potentially going to be of more value than sensitivity). There is some subjectivity here in what will work for you, depending on your size, foot strength and general technique, but if I were a small person I probably wouldn’t look at the stiffer range of shoe at all. Despite being at the other end of the spectrum, I still generally prefer the softer shoes available, though I also favour steep climbing generally and don’t do a lot of longer routes where foot fatigue becomes a performance issue in a soft shoe. Nevertheless, I still think there is a time and place for a stiff shoe as part of the toolbox, especially if you are reasonably new to climbing and larger in size for a climber.

This is the general rule I’d look at: if from the above analysis you are looking for a flat profile, then it is ok for a shoe to have a moderate amount of stiffness and support, especially if you are heavy or prioritising edging performance versus smearing. The more downturned you go, the less sense it makes for the shoe to be stiff as it isn’t going to be sensitive or be able to adapt to the shape of a dicey steep smear. On the odd occasion, you might be climbing something steep and have to stand on a small edge, but it make less sense to wear a stiff shoe even for that case, as this will compromise the performance on the rest of the route (or boulder problem) more than a soft shoe will on that particular move. If it is the crux, you might suck it up and wear something stiffer, but generally speaking, it is best to err on the side of softness than the other way around—as your feet will get stronger as required and your footwork will improve with greater sensitivity.

Velcro, slipper or lace up:

Some people simply don’t have the patience for lace-ups. People like Steve McClure get around this by wearing lace-ups and not bothering to tie the laces. Others will argue that lace-ups provide a more secure and adjustable fit, but if the shoe fits well enough, then some kind of velcro closure should really be enough. Pure slippers (with an elasticised opening and otherwise no closure system) have become slightly less common since steep climbing became more and more popular, as they rarely provide the kind of heel retention on aggressive heel hooks that you get from a more secure shoe. You don’t want to fall off because your shoe came off your heel. Having said that, I’ve had pairs of slippers for steep climbing that haven’t suffered from this problem, so fit is still king.

All options are viable, so long as you can get the secure fit you should be looking for. It is worth noting that both velcro and laces can wear out, but laces can at least be replaced quite easily.

Rand, slingshot heels and toe rubber:

The rand is the rubber around the outside perimeter of the shoe and protects the uppers from wearing by running against the rock where they join the sole. There are only a couple of things worth noting about this. The first is the No Edge technology on some of La Sportiva’s highest performance models like the Futura, Genius and Theory. This is where the sole of the shoe wraps around continuously to cover part of the upper and form the rand without needing a separate piece of rubber. Delaminating of the sole from the rand is possible in high wear areas if the adhesive begins to fail, but this technique solves that problem by providing a continuous piece of rubber in the contact area and better uniformity. This was also touted as providing superior adherence on some types of hold as the tip of your shoe rolls forward before lifting off a foothold. However, the added thickness of the sole rubber (~4mm) on top of the rand’s thickness (a rand is still used underneath the No Edge sole) does mean that when used on the front point of the shoe the tip of your toe is necessarily further away from the rock and on small footholds this is likely to make a difference. On some styles of climbing this isn’t an issue (generally the steeper it is the less likely) and the adherence on transition is going to be more useful. But I find my Futuras a little clunky for this reason (some people love them). On something like the newer Theory shoe, the No Edge is only in place on the inside edge around the ball of your foot, rather than the front tip. This is great for engaging on heel-toe cams and for toe-hooking—I think the implementation on that particular shoe is fantastic.

The other aspect of the rand is known as the ‘slingshot heel’ rand technique where the front rand from the toe box forms a continuous loop right around the shoe and over the achilles tendon attachment above your heel bone. This serves to tension the whole shoe and push your toes into the front. When done just right, this gives the shoe lasting performance and added heel retention. However, if too tight it can be very uncomfortable and pressure your achilles tendon. There should be no stitching or inconsistency of the liner material on the inside of the shoe in this area, or it can cause blisters and discomfort.

Rubber added on the top of the toes gives protection and grip for toe hooking and added sex appeal for the shoe. Think of this as a front spoiler for your sports car. In New Zealand, we don’t have so much steep climbing that toe hooking is that common, at least outdoors. I can probably count all of the essential toe hook moves I’ve done on rock in New Zealand on one hand, but maybe that’s just because my leg was too long for Speed Freak at Turakirae Head. I could probably double the number of climbs I’ve used one on if I could do that particular example. Regardless, something I haven’t seen discussed is that this rubber on top of the toe box also stops the material in that area stretching and so helps to provide a lasting good fit (I’ve been adding a ground-up rubber and glue mixture to the top of the toe boxes of the unlined-leather La Sportiva Cobras for around fifteen years for this very reason). This is great if the fit is right from new, but if your last pair of shoes didn’t have toe rubber and stretched a lot, don’t buy a new tight pair with rubber over the toe and expect them to stretch out to fit—they might not.

Comfort expectations:

As I said above, the comfort to performance ratio is subjective. Twenty years ago, we used to buy shoes extremely tight, knowing that after an agonising wearing-in process they would stretch to a point where you had a performance fit. The materials and design of shoes have got better since then, and a shoe won’t change as much during its lifespan. This is great, because now you can buy a shoe that performs pretty well straight out of the box and you don’t have to go through a painful wearing-in process. Having said that, I’d still expect a bit of discomfort on the first few wears of a shoe in order to end up with a high performance fit. But there is a spectrum here that runs from too tight/bad performance through snugly tight/good performance out to comfy fit/low performance and eventually ‘I can wear these all day, but they may as well be sneakers’. You’ve got to figure out what works best for you. You won’t have fun or be able to climb properly if your shoes are too tight and painful, but if you buy them too loose then you’ll notice you struggle to stand on things that others can and that might not be fun either!

Of course, how much a shoe stretches will depend on materials and the better the shoe fits your foot, the less it will need to stretch. The shoes that fit me best don’t feel uncomfortable when I first put them on and give great performance, it is only after some time wearing them that the build up of pressure on the toes means I need to take them off. If your shoes are uncomfortable immediately and not brand new, then they are probably a bad fit or too small.

Another rule of thumb is that the stiffer a shoe is, the less tight it needs to be. I bought a pair of La Sportiva’s rock-hard TC Pros in the biggest size available (46) and unfortunately this is a very tight performance fit in a shoe that a lot of people recommend buying 1-2 sizes bigger than you would usually wear—as this allows great all-day performance. Stiff shoes are generally going to have less ‘give’ while providing more support, so you can get away with them being a little less tight. Softer shoes are usually going to have a bit more elasticity so they can be more snug without compromising using your foot. They will also be fairly sloppy if not tight enough and so give your foot very little useful support.

To resole or not to resole:

I got my first few pairs of rock shoes resoled but haven’t bothered for about 15 years. I think the price of a resole versus a new shoe (always wait for the sale) fails the cost benefit analysis because they don’t usually perform nearly as well after a resole. However, if your uppers are still in really good condition, you haven’t gone through the rand at the front of the shoe and the fit is still really good, there is no reason not to get a resole and extend the life of your shoes. Less waste is good. I generally find that the uppers and midsole on my shoes are close enough to giving out by the time the sole wears through that I wouldn’t get through another sole before they are too blown-out to be useful. But remember I am a heavyweight, your experience could well be different.

If you’ve made it this far, hopefully you have learned something useful that will help in selecting your next pair of shoes. Below are a few reviews of particular models that have found good use with experienced and skilful climbers. Stay tuned for a follow-up article that will give a brief overview of the major brands, discuss how many different pairs of shoes you might actually need and feature some more guest reviews.

-Tom Hoyle

Five Ten/Adidas Aleon - John Palmer

I have spent a lot of my rock climbing time in New Zealand hanging out with people who (like me) probably take it more seriously than they should. One manifestation of that affliction is rock shoe snobbery. On some level, that snobbery is a conceit. On another level, it is a legitimate reflection of the fact that rock shoes are the single most influential piece of climbing equipment a climber will ever own, at least insofar as climbing performance is concerned. They are aid climbing.

I am probably a shoe snob too. I have never owned and will never own Saltics or Ocuns. Yet, generally, I find myself on the receiving end when it comes to shoe choice criticism.

In the early days, it was the old skool Pinks – the early version of the famous Five Ten Anasazi lace-ups. I couldn’t deny that they had a ludicrously designed heel cup that fitted nobody. I just didn’t care. Pinks were excellent edging and smearing shoes, ideal for the climbs that I wanted to try. And when I did heel hook, they stuck. I have the photos (and the tick) on Kaiser Soze (31) to prove it.

Next it was the Arrowhead – Five Ten’s racing red, down-turned version of the Anasazi Velcro. This time the taunts centred on the fact that the particular rubber (so-called Onyx) used by Five Ten on the Arrowhead was inferior to Five Ten’s so-called C4 rubber. C4. Onyx. I didn’t notice the difference to be honest. All I noticed was that the Arrowheads were still sticking to the rock as I clipped the anchor on Twilight Of The Gods and Ride Of The Valkyries, two of my hardest ever ascents.

More recently, the barbs have been aimed at my pair of Five Ten Aleons. I came to own a pair of Aleons by accident. A friend had ordered them online, hoping that the fact that they were designed by the legendary Fred Nicole might rub off on his boulder grades. Unfortunately for him, they were a bit tight out of the box. Luckily for him, I had a new pair of Pinks that were (in customary Five Ten fashion) simultaneously the same size and a completely different (larger) size to my previous pair of Pinks. He talked me into a swap. And so it began.

The Aleons are a moderately stiff, heavily rubbered, down-turned and pointy-toed shoe in any colour you want as long as it is red. Think: Five Ten’s version of the very-popular La Sportiva Solution.

They come with an integrated sock-like inner, which appears to serve no useful purpose other than to make you look like you have socks on when climbing. I am told it looks ridiculous but these things are always relative.

The rubber is C4. Not Onyx. I still can’t tell the difference. However, one difference between the Arrowhead and the Aleon is the extensive wrap of precision-cut rubber on the upper, which makes cheating on toe hooks and heel-toe scums a breeze.

The shape is my favourite aspect of the shoe. The asymmetric down-turned last gives the shoe plenty of horsepower on steep terrain. The toe box is pointy at the front, giving great edge and pocket precision, but widens quickly to make that tight fit just a touch more comfortable, especially for people with broad feet. And, finally, the low volume, soft rubber heel actually resembles the shape of a human heel and, from my own experience, seems to operate well in most heel hooking scenarios.

I read somewhere that the front half of the last is reinforced by metal rods forged by Fred Nicole with his bare hands. I’m sceptical, however, I have found that, even after months of wear and tear, my pair have retained a good level of stiffness. That means the Aleon never excels at smearing but there will be other shoes in your quiver for that.

In the past 18 months, I have climbed several routes near my personal limit in the Aleons, across a range of rock types and angles and much to the disbelief of my naysayer friends (disbelief that was, at least in part, because of the shoes). Overall, I have found the Aleons to be a comfortable, versatile and well-performing rock shoe.

Does that make them good? What makes a good rock shoe? Well, I think a good rock shoe is one that makes you climb better than you are and, on that measure, the Aleons get a big chalky tick. Best shoes I never bought.

Ocun Oxi Women's - Cirrus Tan

For the first few years of my climbing, I thought my toes were meant to be in pain. I had formed calluses on the top of my toes from cramming my feet in tiny shoes that didn’t fit me. As someone fairly new in the game, I too thought this was needed if I wanted to climb harder. Over the years, I have tried many different brands and I never felt any of them fit my foot shape perfectly.

Two years ago, I tried Ocun Oxis and this was a game changer. They fit snugly but didn’t hurt. I went a little bigger than previously, so they were basically ready to be worn straight away, but I never feel compromised on performance. The narrow heel fits me well, meaning I can really crank on heel hooks without feeling the heel slip off. The shoe is relatively aggressive, with ample toe rubber which is effective on steep boulders and routes where I am toe hooking. I can happily keep them on for most of my indoor bouldering sessions, which just makes climbing more enjoyable. Outdoors, they are quick to take off and put on, with just one Velcro strap to deal with.

Because they are more of an aggressive, downturned shoe, this can mean that on slabs they are not as effective. Although the edges and rubber on them are solid for small footholds, they are not as flexible if I want to smear on slabs. For me though, this is such a small negative that the Ocun Oxis are still my go-to. In bouldering competitions, we are guaranteed a mixture of boulders with different styles. I still only use the Ocun Oxis for all boulders, as I believe they are a good enough all rounder for what I need.

If you are looking for some climbing shoes, take time to try a bunch of brands and styles on. Keep in mind there is rarely a shoe that will be ideal on all terrains. Find something that feels snug for your feet. Do not go crazy tight and painful. Remember, climbing should be enjoyable and your shoes should facilitate with that!

*Cirrus Tan is supported by Ocun.

Five Ten Blackwing Women's - Erin Stewart

I distinctly remember the first time I ever experienced Five Ten Stealth rubber. In fact I can even recall the exact date—8 0ctober 2012—because those shoes got me the send of a project.

I used to wear Scarpa Veloces (having previously tried and ditched a variety of La Sportivas). Generally a great shoe—well-made, well-fitting, comfortable—but not a winner for climbing at Castle Hill. I spent most of my time popping off footholds and thought anyone who could stand on tiny limestone smears was some kind of wizard engaging in dark magic.

The project’s feet started on one imaginary smear, up to a high, slightly-less-imaginary smeary groove. I popped off both of these feet countless times. Eventually, Derek got fed up watching me flail and demanded I swap shoes with him, handing me his pair of Five Ten Jet 7s. I sent the proj first go in those puppies, and so began a love affair with Five Ten. Nowadays, my modest shoe collection consists of a few different Anasazis, Arrowheads, the Jet 7s, and three pairs of the all time favourite—Blackwings.

The women's Blackwings are a low volume, soft, semi-downturned, high performance style with double velcro closure that allows a better fit for folk with skinny feet. The semi-downturn is designed for steep routes and pockets allowing you to pull in hard on your toes, but the lack of a stiff midsole means they also excel on smeary technical feet. They have a narrow fitting heel with an extra rubber layer that catches well when heel hooking, although with minimal rubber on the top of the toe box they aren’t designed for toe hooking.

While many people wouldn’t consider them a slab shoe I find the softness, downturn and ultra sticky rubber excellent for very small or smeary footwork - they never slip. The softness allows you to feel every feature of the rock and therefore you can place more precisely and stand harder. Any foothold with a slight edge and these shoes will stick like glue.

While the one perfect shoe for everything and everyone doesn’t exist, if you have low volume, narrow feet and climb on either steeper terrain or technical tiny feet then this style is a winner.

Unparallel Up Rise VCS - Alec McCallum

Climbing shoes are the most important piece of equipment a climber can own. When wandering up a low angle slab, they are the sole connection between you and the rock and all that is keeping you from sliding down in shame towards the ground. The Unparallel Up Rise excels at the two main purposes climbing shoes are for. Getting you up rad rock climbs and more importantly making sure you look good doing it.

Climbing shoes are the most important piece of equipment a climber can own. When wandering up a low angle slab, they are the sole connection between you and the rock and all that is keeping you from sliding down in shame towards the ground. The Unparallel Up Rise excels at the two main purposes climbing shoes are for. Getting you up rad rock climbs and more importantly making sure you look good doing it.

They seem to be custom made for climbing in Castle Hill Basin. Plastered with sticky Unparallel rubber, they are perfect for the smooth, frictionless climbing at ‘The Hill’. The flat sole ensures maximal rubber contact on the rock. Essential for the high quantity of slabs.

Whilst ideal as a shoe for slabs and faces, it can also perform well on steeper terrain. With a fantastic heel and rubber on upper for toe hooking.

They have been my favourite shoes since I first tried them and I'm sure they will be until the annoying day comes where they are discontinued.

Five Ten/Adidas Quantum Lace - Tom Hoyle

When the Quantum Lace first appeared in Five Ten's shoe line up in 2013 it was as a newly-designed shoe in a fairly bold purple colour with strange ribbing on the upper. The toe box design was relatively symmetrical and rounded, though this was not a shoe from Five Ten's storied Anasazi last. Bob Keegan convinced John Palmer they looked like a lace-up version of his beloved Arrowheads, so he bought a pair. John did not get along well with the shoes and eventually gave them away to Bob with a message along the lines of, 'if you think they're so good, you should use them'. Never one to shy away from the opportunity to one-up John, Bob persisted in wearing the shoes at every Engine Room training session when John was present. Unfortunately for Bob, his opportunity to showboat was drastically undermined by the way the Quantums would seem to pop off footholds unexpectedly. The shoes were written off as trash by all of us, though we kept up the pretence of shaming Bob for his poor footwork.

When Five Ten launched a new version of the Quantum Lace I took little notice, other than noting they'd improved the colour to an azure blue that I would probably actually be able to wear in public. John pointed out to me that the shoe was now slightly downturned and more pointy and asymmetrical in the toe box area than the previous version—or the Anasazi shoes (which I had never got along that well with). Suspicious that John was trying to comically perpetuate the 'Quantum is a great shoe' gag, I investigated a bit more and saw that this shoe had been made in detailed consultation with the Huber brothers, both of whom have very impressive climbing resumes. It became clear that this was a complete redesign, basically another new shoe for which Five Ten had inexplicably recycled the far-from-being-revered Quantum naming (they are closer in toe box shape to the Verdon than the original Quantum, though slightly downturned rather than flat). But it was indeed a Quantum leap forward—perhaps they had needed to make a bad shoe first to allow for that marketing gag to work. They'd even switched from the Stealth Onyx sole, to the softer but stickier C4.

The blue Quantum Lace is what I would call a high achieving allrounder. It has a slight downturn, so you can use it to toe in on steep terrain, though it isn't going to do so well as a softer, more sensitive shoe. I would say the level of downturn is appropriate, because its moderate nature allows the shoe to still excel at edging and smearing. The Five Ten designers have identified that if you are climbing terrain where you really need the most aggressive downturn, you are probably going to swap to a softer shoe. Accepting that this shoe isn't aimed at that category allowed them to give it a reasonable amount of structure, so the foot is well supported on face climbs. But they've also resisted making it into a total brick, it has a lined synthetic upper but the midsole isn't too stiff, so after a wearing in period it has what I think is a really nice balance between sensitivity and support. This lasts pretty well through the life of the shoe, though it must be the case that the sole provides a bit of structure beyond the midsole, as they are a fair bit stiffer when new and become more pliable as the sole wears down. For this reason I run a two-pair system with an older well-worn pair getting use at the same time as a newer pair with crisp edges. This also gives me some protection from Five Ten's general strategy of randomly discontinuing popular models (I currently own three pairs).

A good allrounder is actually quite a hard shoe to make, if you are going really specific then the design choices become more clear. But if you want a shoe to perform at a high level across a range of terrain then getting just the right balance between profile, stiffness and the shape of a shoe is a delicate series of choices. For me, the Quantum lace strikes the right balance of these attributes for my climbing. It is pointy and asymmetrical enough in the toe box for my foot shape and while it might not be the best ever fit for my foot (that title would probably go to the La Sportiva Python, though it is a much more supple shoe), it is pretty close and considerably better than a lot of the Five Ten shapes, probably because it is slightly wider than their other downturned shoes. If I am on consistently steep terrain like The Cave, or climbing indoors, I'll opt for a much softer slipper, but for anything else and general onsighting, I usually choose the Quantum as it's going to give me the best performance across the widest range of footholds I'm likely to encounter.