Expedition Report - Pasage Du Desir

“You may think because I’m a climber that I came to Font to climb. You couldn't be more wrong. This is why I came, the pastries. The daily routine of a patisserie stop before the blocs is the highlight of my day, it’s all downhill from there. No amount of 8a’s can come close to the satisfaction you get from a gooey almond croissant, the full mouth coating of a pave pistache framboise or the pleasure of the crisp crust and incomprehensibly soft inner of a baguette. You don't get this sort of quality elsewhere. I’m coming back to Font, but not for the boulders.”

I wrote the previous paragraph four years ago at the end of a European climbing holiday. What I knew then, as I still know now, was that even though the climbing in this forest is possibly the best bouldering in the world (only matched by the lush tussock lands that lie between Craigieburn forest and Porters Pass, in a small island in the southern reaches of the Pacific Ocean), the baked delights found in this forest surpass the quality of the bouldering.

There are, I imagine, two types of people in this world, those that go into a bakery and get the same bread and pastry because they know what delight they seek for their day, and there are those that venture into a bakery and peruse the selection, decide on some item of baked good that they had not experienced before and select that even if it does not look as delicious as the standard purchase, but selecting so out of a necessity to discover what else is out there.

Upon writing the previous paragraph I realised that in fact there are not just two types of people in this world but a spectrum of pastry consumers, with the aforementioned humans at either end. For instance, I would identify as being towards the “different pastry every day” end of the spectrum, however, when visiting a new boulangerie, in a new town, in a new area of this idyllic forest, I am always drawn to judging the quality of all baked goods in the newly experienced bakery by the quality of their Croissant aux Almonde.

The almond croissant is the staple of sweet baked goods in the forest. Every boulangerie you visit will do their own version of one and these vary from highly structured croissants with custard-like almond filling to a mess of butter, sugar and almond that needs to be scraped off the baking tray. Yesterday, at the bakery located a short walk from our accommodation, I purchased two freshly baked almond croissants along with the bread for the day. These croissants were yet to be displayed in the cabinet and still lay decompressing on the baking tray. Their position on the tray would mimic our bodies later in the day as we devoured them and then proceeded to dissolve into the boulder pads. Quite like a cup of black coffee and a cigarette, eating one of these gives you an odd, relaxed energy. As I lay there on the boulder pad I could feel the block and a half of butter I’d just eaten oozing through my muscles, whilst the cup of sugar pumped through my veins—sending my heart into overdrive. For some people, an almond croissant should be eaten in two sittings.

It is hard to say whether or not these delights enhance or hinder climbing performance. They are surely a day's enjoyment enhancer, it is a rare day when some sort of baked delight is not consumed in the forest. However, climbing ability generally deteriorates after consumption. Luckily for us, there is a multitude of high-quality, low-difficulty climbing in this forest. That attribute might actually be the forest's defining quality: no matter how difficult the climbing is, whether it's mutant, hard-bod difficulty or shoulder-high toddler level, the features that make up the challenge are incredible. Large rounded tumours of sandstone bubble out of the surface, giving you these three-dimensional bulbs to cling to, the tops of the boulders often take on the form of a tortoises shell, in texture and roundness, but then there are times when the tortoise shell is pulled and distorted creating these beautiful ergonomic jugs and pinches, and other times where patina plating covers the rock, a marble kitchen countertop stuck to the wall, sheer and pristine. The edges of the counter give you crimps which vary in pleasantness, but are all wonderful features.

These qualities have enabled us to do something which I’ve been pining for since the start of this trip, mid range climbing, and a lot of it. Every day after trying a harder bloc, or not trying one at all, we’ve been able to go and tussle with these smaller challenges which host their own beautiful qualities. In other areas, at different stages of this trip, our bouldering efforts have been restricted to a handful of climbs and generally one or two at each grade, and so being able to go climbing loads at any grade we desire is an aspect of Fontainebleau I thoroughly enjoy.

Yesterday I ate a plain croissant which changed my life and then climbed one of the best slabs in Fontainebleau. On previous visits to the forest, friends of mine had told me stories of the perfect croissant, the pinnacle of baking. I had dismissed these claims as I had been hooked by the glucose high of the almond variety, however, on this trip I was able to understand what they meant. This croissant, enjoyed at an esoteric crag under the leafless branches of the forest canopy, would appear at a glance to be overdone, too much time in the oven. The crust of the flakey pastry took on a dark brown colour, more so than one would expect for a croissant. However, this alluded to one of its most delightful qualities: burnt butter. Heated just to the point to enrich the flavour, but not too much so that it tarnished its smoothness. Each bite taken from the croissant would leave it structurally unstable, allowing the rolls that were once tightened into its classic shape to fall outwards, unrolling, asking to be consumed. Bite after bite, this pastry amazed me: from how the flavours changed as you moved your way through the croissant, burnt butter at the edges to the silky centre section, to how its simplicity of flavour creates such a satisfying experience, no need for the unique taste of obscure combinations or expensive delicacies, all that was present was simple, quality goods.

I won't forget eating that croissant, I won't forget its obtuse flavour coating my mouth, I won't forget my surprise at its quality, nor will I forget climbing the slab afterwards. A pristine sandstone rounded arête with moss creeping its way over the unclimbed areas. Sitting at around six Dereks high, and at a very accessible grade, it was the perfect chaser to my croissant affair. The nature of slab climbing outside of the Basin is quite a different experience. Whereas at home, the perfect slab follows the strongest of forms, with no imperfections or fractures, overseas slab climbing relies on weakness in the rock to form little edges to stand on. The patina plating that I talked about in previous paragraphs can create some incredible slab experiences. On the face of the patina, there is no friction or features, although the edges create these little feet that, with the correct pair of boots, are like little steps on a staircase. This slab, Ma Que Bella (6B+/V4), had the perfect distribution of these features, allowing you to tick tack your way up to quite a height, until they promptly run out and you are required to press downwards with your thumbs, moving your feet high enough until you can ultimately reach the rounded lip of the block. It’s everything you could want in a slab in Fontainebleau.

Today after I wrote the paragraphs detailing the delights of my plain croissant and the ascent of the slab in the woods, I made the journey to the local boulangerie for another dose of our daily bread. Rain had fallen overnight with indifference to our desires to climb the boulders that inhabit the forest. Despite this, the sky was clear of clouds and the only remnants of the night’s weather were the puddles dispersed surprisingly evenly down the one way lane that our home resides on. The sun, which had just risen over the horizon, could not yet reach these puddles due to the orientation of the road being perpendicular to the trajectory of the sun and the height and proximity of the stone walls which border this lane, so my walk is draped in shadow. At the end of the lane, where my route was to take a left turn on my path to the boulangerie, the sun sparkled enticingly, reflecting off the grains of the sandstone cobbled street. The air was cold, due to a persistent northerly breeze, which has been with us for the majority of our time in Fontainebleau but is by no means a common occurrence in the forest, despite the frigidity of the breeze, the sun was doing a commendable job in warming the little town.

Once inside the bakery, I fumbled with my French and ordered a loaf of Demi Complet Grain and one of their fresh, off the tray croissants and dropped 3.40 euro into the palm of a good-natured, middle-aged lady whose English is equally as poor as my French. Our interactions usually consist of one or two poorly pronounced words in each other's language, smiles and prolonged periods of silence. I can only hope that by the end of our month-long stay in this town our interactions might become more conversational.

Standing on the corner of the main street in a patch of sun that had snuck its way between the gables of two houses, I ate my croissant in silence and dreamed that it would get better. I couldn’t describe why this particular croissant was not of comparable quality to the day before, but it was not up to standard. The perfect croissant lives on in memory, and sub par imitations only dilute that memory.

I’m well aware that both the purpose of this trip and the publisher of these certain reports revolve around the activity of rock climbing, and so I feel as though I must indulge at least a small amount into some sort of climbing-related discussion. The issue I’ve had with writing these pieces and including a lot of climbing content in them is that I didn’t want them to come across as a list of summits for a trip which is not about the length of our ticklist at the end of the day. I would much rather tell a story on a certain one or two climbs, which I have attempted to do in previous reports. However, in the forest there were so many incredible moments of good rock climbing, good people and good stone that it seemed silly to summarise it in a list, or even still, a story of a single boulder. Nevertheless, this is not a New Zealand Baking Club report and so I will endeavour to write about two ascents which have some sort of personal significance to the expeditionaries.

For Isaac, coming back to the forest meant returning to a boulder which had denied him success on his previous journey. The denial wasn't due to lack of ability to climb the boulder, it was down to luck, which in some ways is more punishing. Isaac has said on multiple occasions that the failure of not being able to do a boulder is more memorable than walking up something that wasn't a challenge for you—the one that got away is a stronger emotion than the one that went too easily. On Délire Onirique (8A+/V12), an incredibly simple bloc, requiring a strong grip and some gymnastic power, Isaac climbed through the hard section of the boulder, only to be denied a summit by the top out slab which, although is not the difficult bit of climbing on this certain rock, is still capable of spitting you off, as it did to him, twice. He wasn't able to get another opportunity for success and so had to finish the trip leaving it undone.

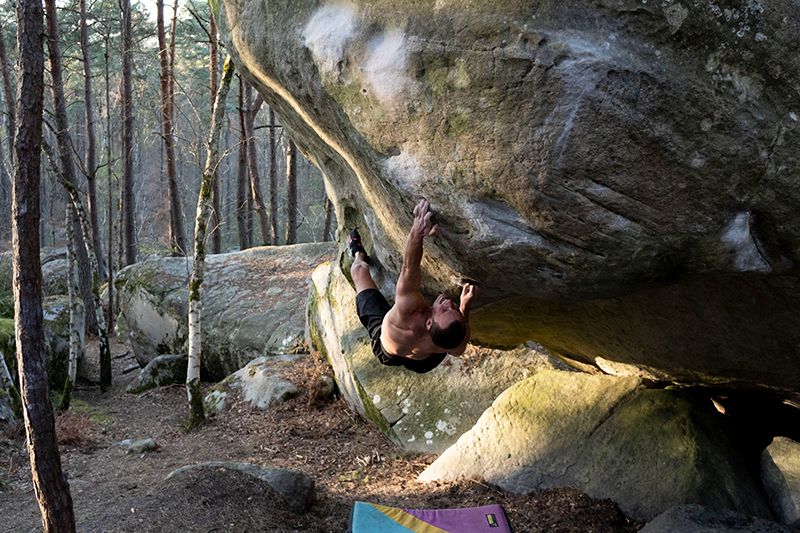

This experience had obviously been replaying in his mind, as it was one of the first things we went to on this trip to Fontainebleau. This time, armed with a rope to inspect the top out manoeuvres, Isaac made sure that he wouldn’t be found in the same situation again. After a couple of warm-up goes on the lower crux, he managed to claw his way through, cutting loose on a vertical sloper in an overhanging wall. Whilst enjoying a fine pain aux chocolat pistache and a familiar cup of tea, from my side on angle of the performance I was able to witness his desperate fist crimping and ‘please not again’ facial expressions as he rounded the belly, until the final realisation, as he dragged himself to secure ground, of success.

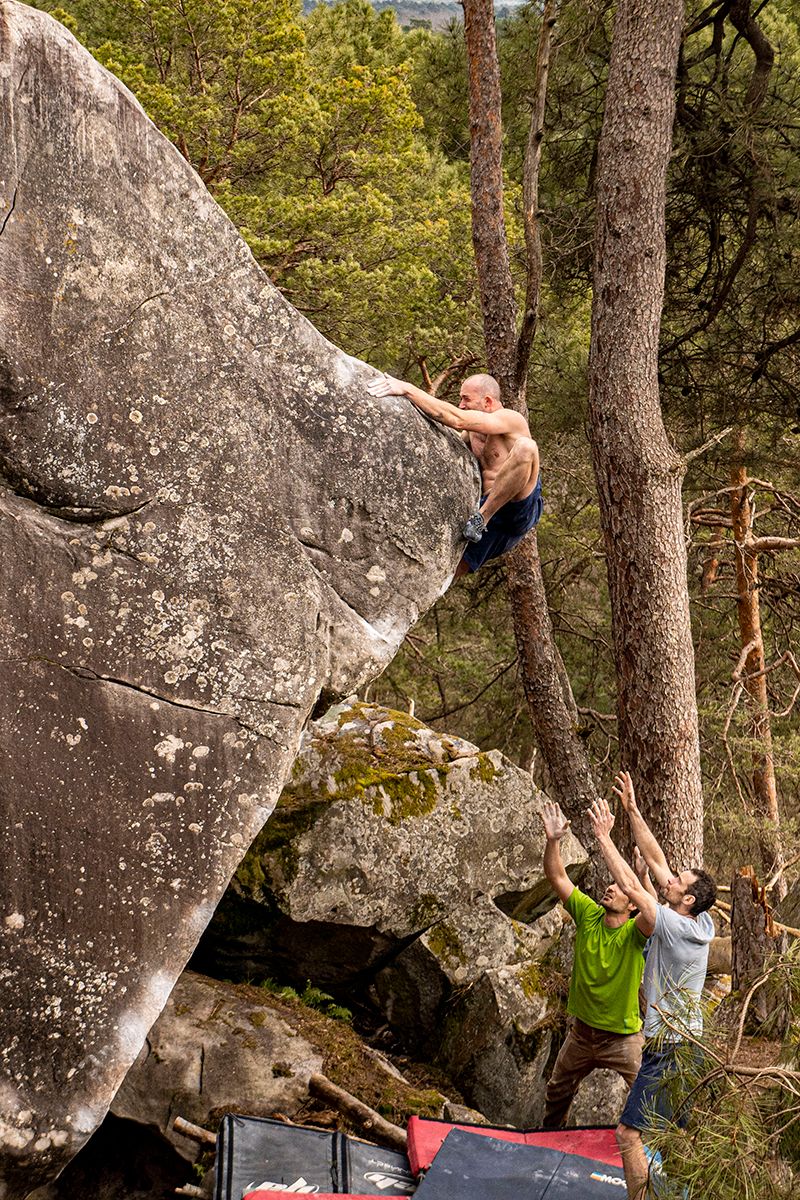

The story of a climb that feels worth telling for me occurred on one of our last days in Fontainebleau. Similarly to Isaac’s climb, I too had encountered this boulder on previous trips to the forest. In fact, my first trip here in 2017 involved spotting Uncle Dave on it on one of his many rest days that turned into ‘climbing-mid-range-boulder’ days. The thing with this problem is that upon first viewing I deemed it as a challenge that I would never be up for, and so to be able to climb the line and to do so comfortably was an unexpected reward from this trip to the forest. Accelerator (7B/V8) is an 8m high arête revolving around secure mid-range climbing at consequential height. There are times where completing climbs of consequence can result in a strong emotional reaction or a dump of adrenaline, which can be quite an overwhelming experience perched on top of a bloc. On this boulder though, there was no part of it that felt overwhelming, what I experienced instead was an incredible satisfaction of climbing with complete security.

When I attempt to remember the experience, which fades ever fuzzier as the days pass, what comes back to me with the most clarity is a foot placement in the crux sequence, putting my foot on the arête, shifting all my weight onto it and feeling with utmost confidence that it wasn’t going anywhere. I hope that as the days go on I will continue to be able to recall that feeling of trust that I felt in that moment, if not, at least I have this written record that at some point in time I could recall a memory of a feeling I felt in a moment on a boulder in a forest far away from my home.

Our time in the forest is already over. I sit writing this in a sub-par cafe in the central district of London, a short pitstop to experience some culture as we make our way back to the Peak District to get one last taste of God’s own stone before this bizarre dream concludes and we head home in a little over two weeks.

-by Matt Corbishley, with images by Isaac Buckley